Today’s Tuesdays With Coleman blog post comes courtesy of Matt Bailey, president of our sister company, Integr8 Research. Integr8 Research is focused solely on new music research, and Matt regularly offers thought leadership to his clients regarding the interpretation of streaming data. In this entry, he explains Retention Rate, a new metric to recognize which songs have staying power.

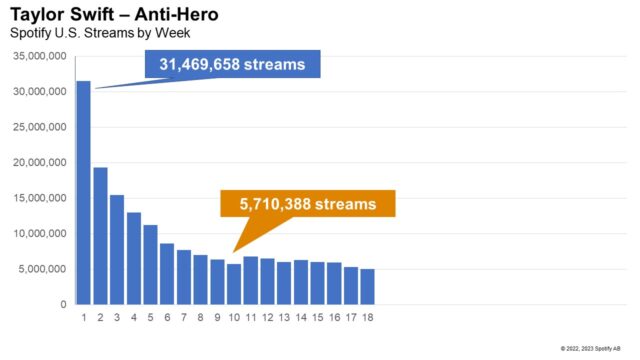

Within a week of its debut, Spotify users in the U.S. played Taylor Swift’s “Anti-Hero” a record-shattering 31 million times—more streams in one week than any other song at the time.

Naturally, CHR and Hot AC stations also immediately added the highly anticipated song by an iconic core artist.

Surely, with record-breaking streaming figures and substantial airplay, “Anti-Hero” was destined to be the most popular song of 2022, as validated by stations’ callout research, right?

Eh.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________

In this post…

- Why record-breaking streaming doesn’t mean big hits for radio

- Introducing Retention Rate

- Streaming peaks reflect the artist’s power; Retention Rate reflects the song’s appeal

- Practical ways to use Retention Rate

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________

WHY RECORD-BREAKING STREAMING DOESN’T TRANSLATE TO BIG HITS FOR RADIO

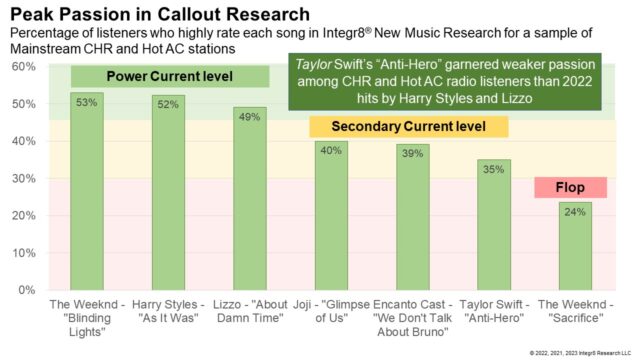

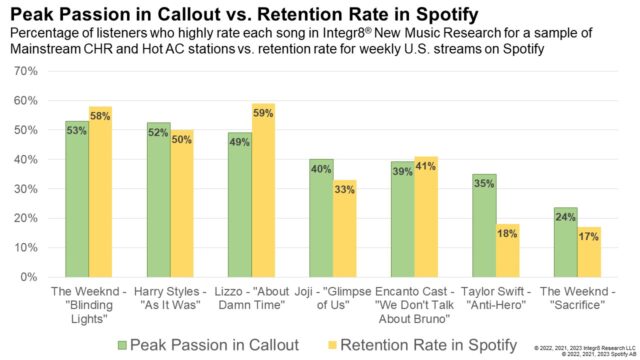

While “Anti-Hero” is hardly a flop, it also hasn’t been the instant home run that “Bad Blood” or “Shake It Off” were. On average, about 35% of CHR and Hot AC listeners said they loved “Anti-Hero” at its peak.

That’s strong enough for a secondary current, but the biggest hits typically see 50% of listeners exhibit strong passion for them using Integr8 New Music Research’s methodology. Harry Styles’ “As It Was” and “About Damn Time” from Lizzo both achieved this metric among our typical clients.

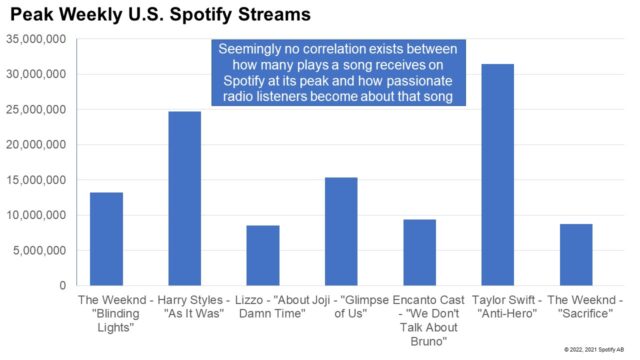

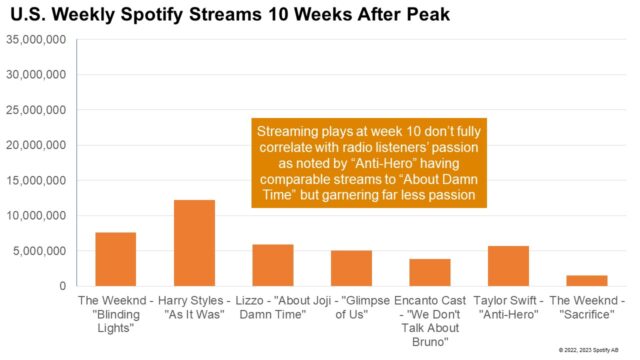

When we examine how these bona fide radio hits performed during their peak week in the U.S. on Spotify, there’s seemingly no correlation at all between streaming plays and passion among radio listeners: “As It Was” had a strong peak week, but Lizzo’s “About Damn Time” maxed out at well under one-third as many streams during its peak week, as did “Anti-Hero.” We will demonstrate this in a bit.

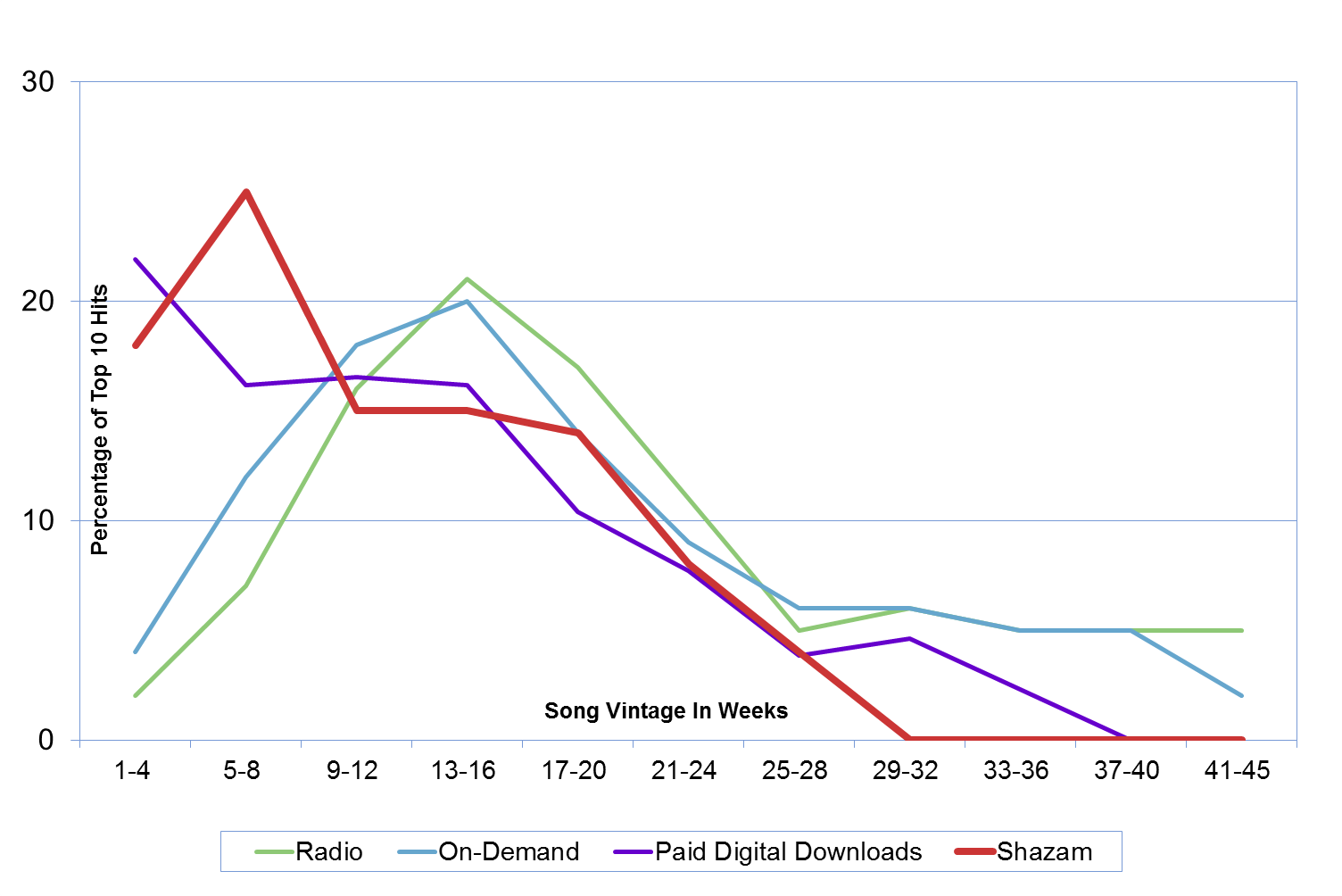

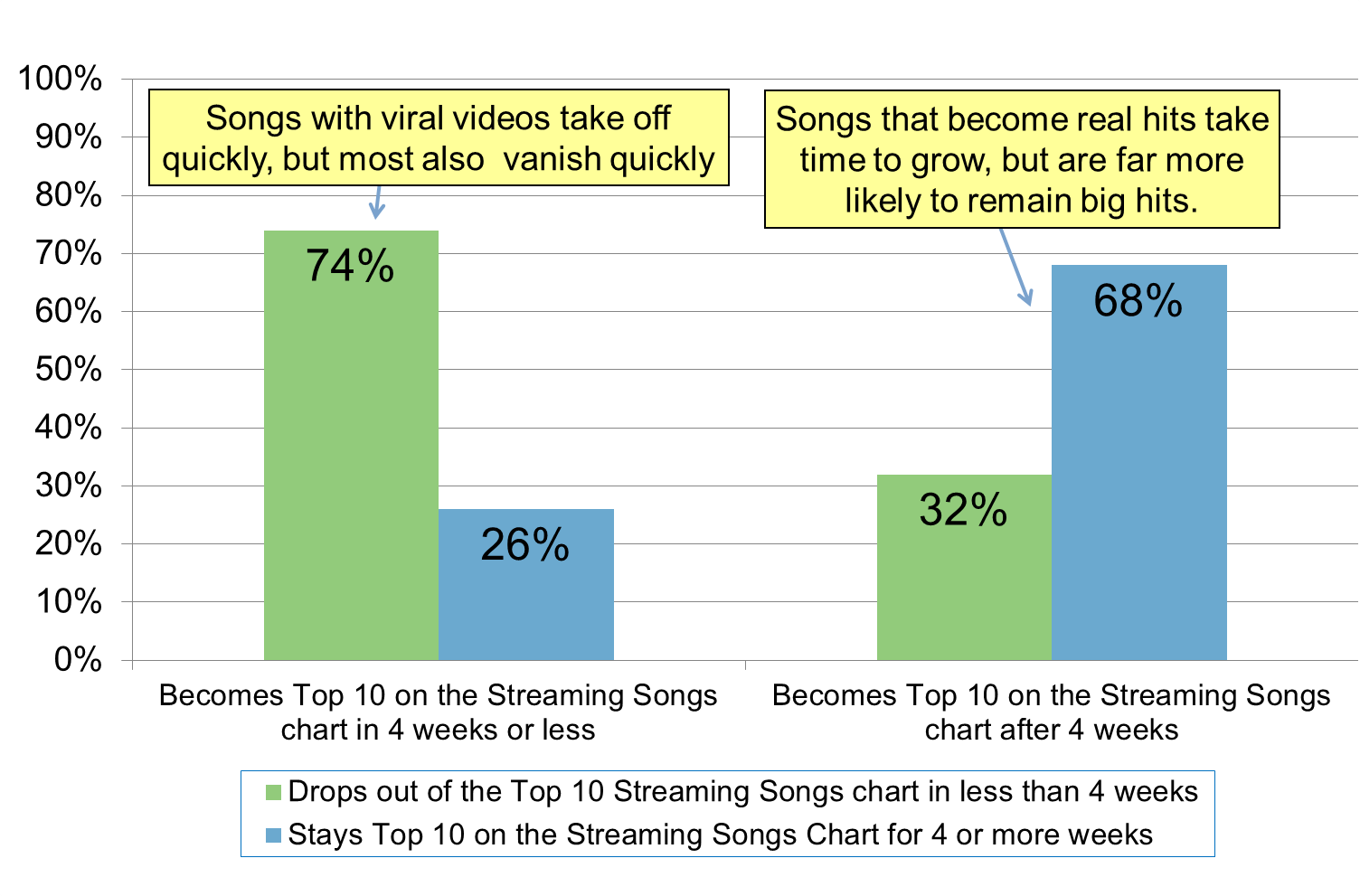

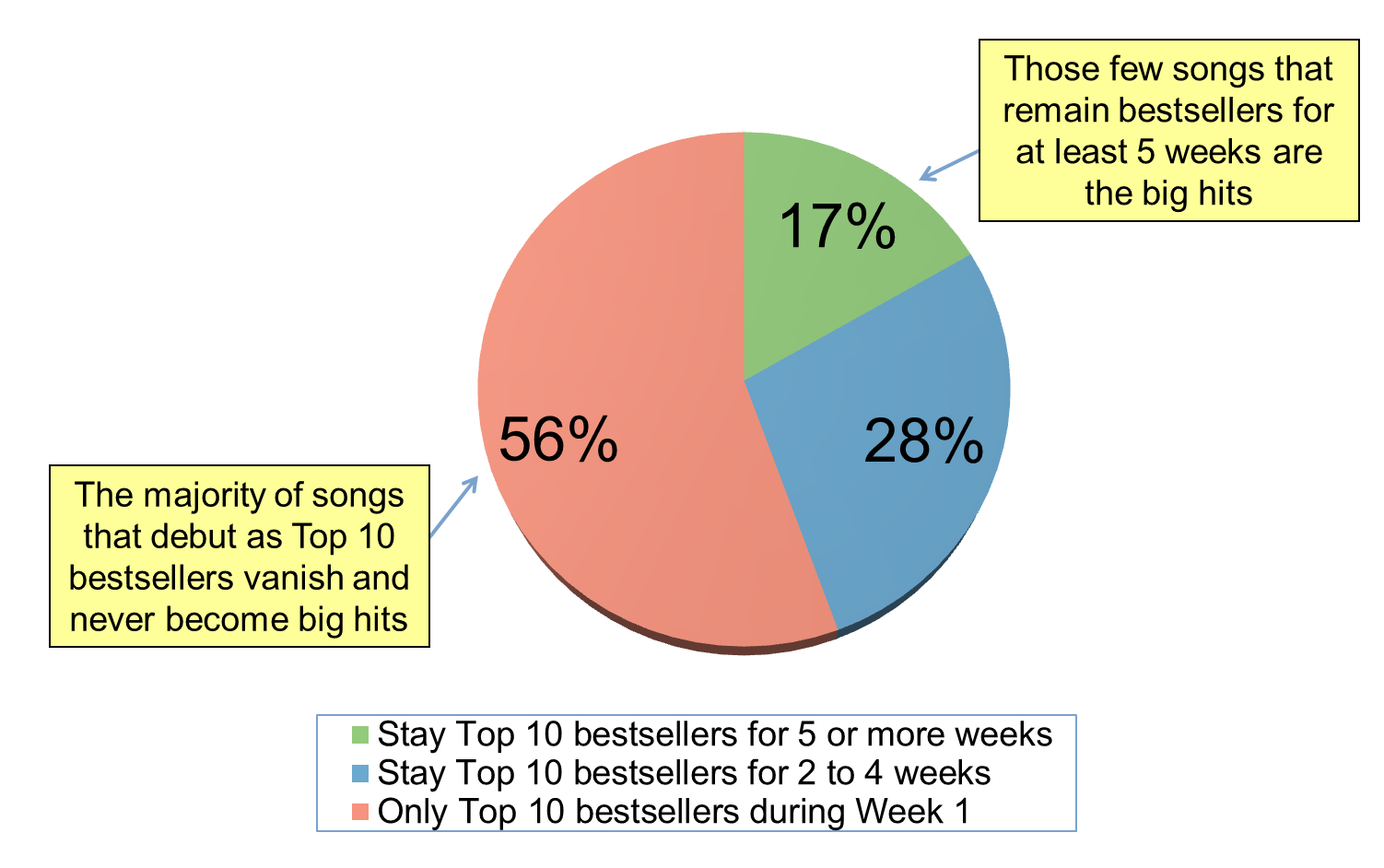

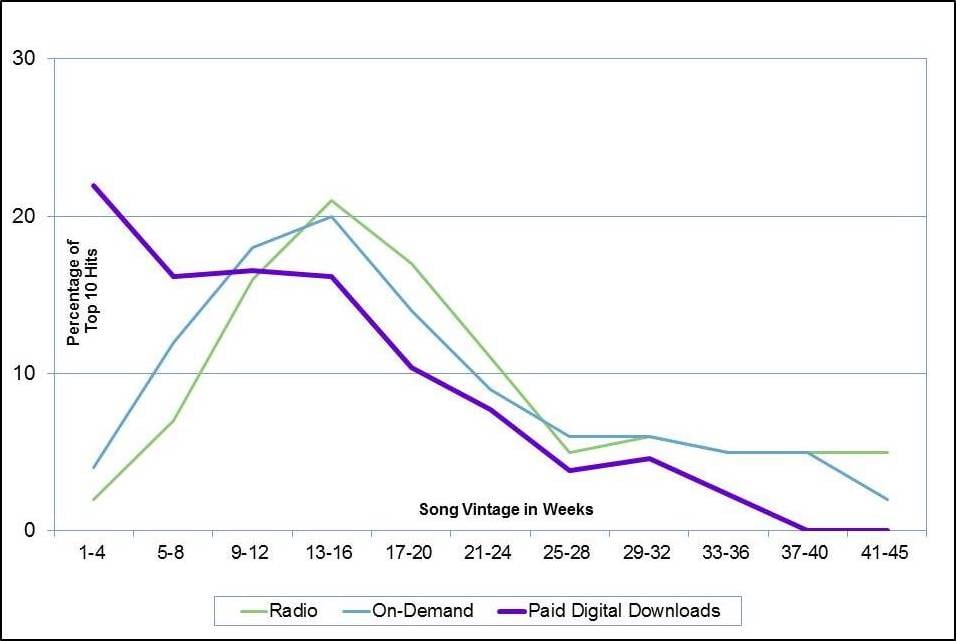

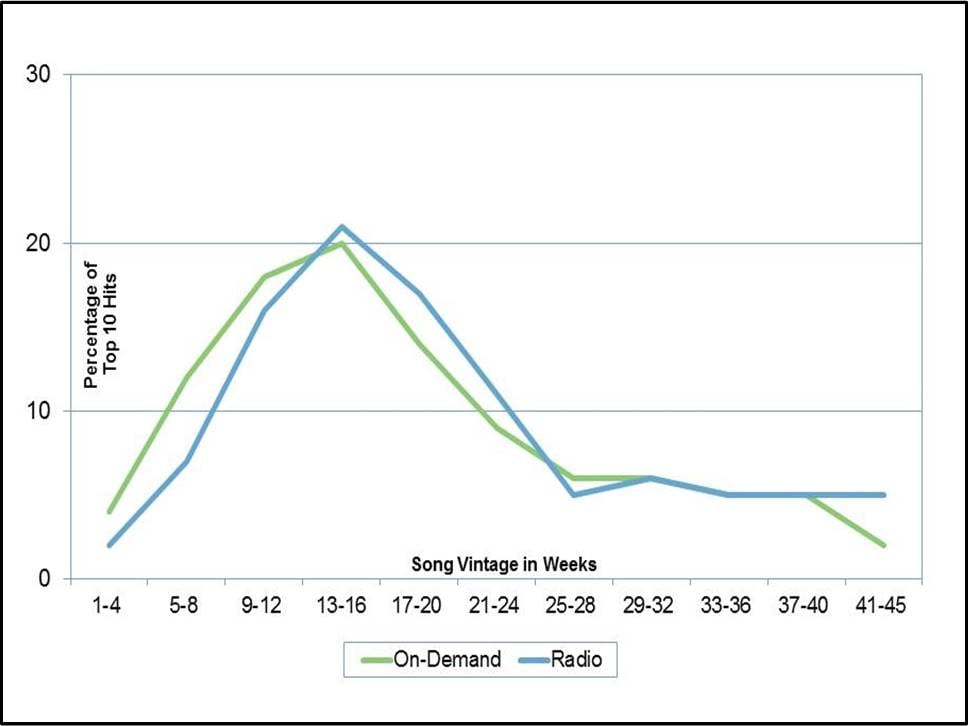

As we’ve noted in several previous posts, streaming data amplifies active fandom, which means a song’s peak week on streaming will often be on or shortly after its debut week. As weeks go by, however, streaming data increasingly reflects the passive fandom of people who discovered the song after its release.

With those behavior patterns in mind, let’s fast-forward to “Anti-Hero’s” 10th week from its peak. (Why 10 weeks? Typical top 10 hits for CHR radio reach their peak passion level among listeners around 10 weeks after debuting.)

Spotify users in the U.S. played “Anti-Hero” about 5.7 million times ten weeks after its record-breaking debut week. That’s still sufficient to be among Spotify’s Top 10 songs in subsequent weeks. However, that’s less than one-fifth as many plays as its debut.

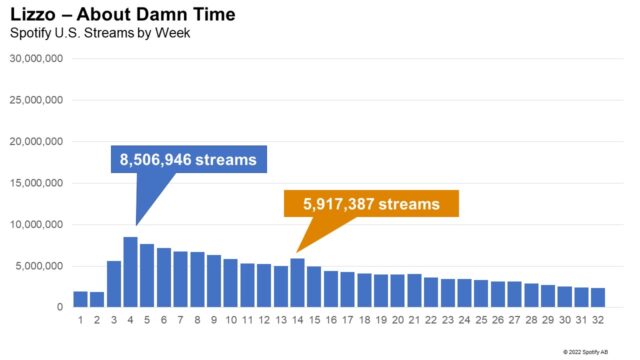

In contrast, Lizzo’s “About Damn Time” only garnered around 8.5 million streams when it peaked in its fourth week. Fast forward 10 weeks, and Lizzo’s summer anthem was still pulling almost 6 million streams.

That puts “About Damn Time” on equal footing with “Anti-Hero” in its 10th week after its peak.

However, simply examining how many times people play a song at 10 weeks doesn’t explain why “About Damn Time” was a much bigger radio hit than “Anti-Hero” has been, either. There’s still no clear correlation between streaming plays and callout passion scores.

If you can’t simply examine how a song performs at its peak and you can’t examine how a song performs once the initial interest in the song dies down, is there any streaming metric that does track with listeners’ passion for a song, as measured in your callout research?

Comparing plays for a song’s peak week on Spotify with its play count 10 weeks after its peak reveals a telling story.

INTRODUCING RETENTION RATE

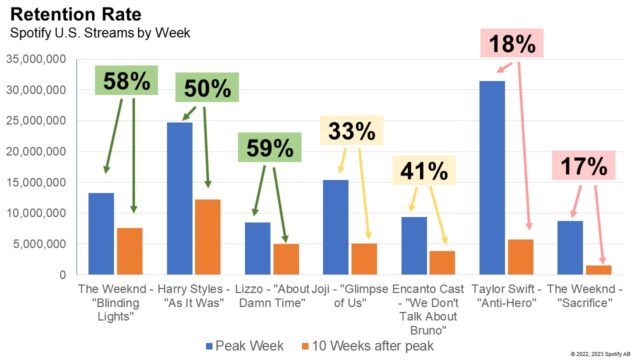

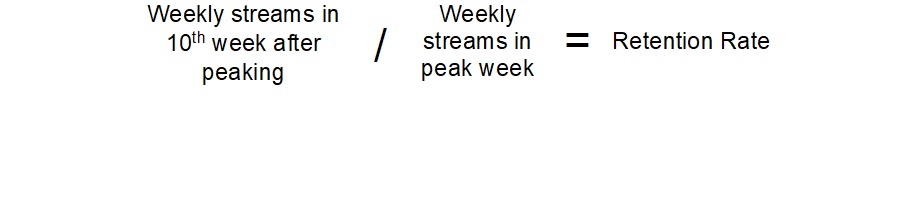

Retention Rate is the ratio of how many times streaming music consumers streamed a song in its 10th week after peaking, compared to how many streamed the song during its peak week.

Comparing the Spotify streaming retention rate for the songs for which we initially examined passion in callout research, we finally begin to see some semblance of a correlating pattern:

Why does Retention Rate make sense?

PEAK STREAMS REFLECT THE POWER OF THE ARTIST’S FAN BASE

A song’s peak streaming week is a measure of how many fans an artist has and how passionate and engaged those fans are. Artists like Harry Styles, Morgan Wallen, Drake, and of course Taylor, have fan bases that run wide and deep. The decision to stream a brand-new song when it drops has everything to do with the artist and nothing to do with the song itself.

In order for a song to continue to garner strong streaming plays, at least one of two things must happen—and generally both:

1) Those diehard artist fans who played the song when it debuted must decide they like it enough to keep playing it week after week.

2) Music fans beyond the artist’s diehard supporters must discover and like the song enough to start streaming it.

For music consumers who like a song but aren’t superfans of the artist, they have to discover the song out in the wild because they’re not explicitly seeking it out: A friend has to tell them to check it out. They have to hear it on a curated streaming playlist. Or perhaps—just maybe—they hear it on the radio.

Usually both #1 and #2 must happen for a song to become a lasting hit.

If an artist’s biggest fans are underwhelmed, it’s unlikely listeners who aren’t even that into the artist will be big fans of the song.

Even for superstar artists like Taylor, there are generally a lot more people who love the song than there are who are hard core fans of the artist. They may “like” the artist, but they’re not buying concert tickets, t-shirts, and fan club memberships.

RETENTION RATE REFLECTS A SONG’S STAYING POWER

Retention rate captures both phenomena. A high Retention Rate means:

- An artist’s biggest fans like the song enough to keep playing it week after week. A low retention rate means those fans may still love their artist, but found the song itself a letdown.

- Retention Rate also reflects new people who have discovered a song after it debuted and have gone to Spotify to play it. A low Retention Rate can indicate few people are discovering the song passively.

In short, while a song’s debut streaming plays is a referendum on the size and passion of an artist’s fan base, a song’s ability to remain among the most streamed songs week after week is more predictive of a song’s hit potential.

PRACTICAL WAYS TO USE THE RETENTION RATE CONCEPT

First, forget about using Retention Rate exactly as we have described it here. Nobody has time to track weekly streaming data for dozens of songs week after week in Excel to precisely calculate a 10-week retention rate.

Heck, I don’t have time to do it, but I find it too much fun to resist.

Fortunately, you don’t have to spend hours creating Excel formulas. Here are some easier signs to examine when you’re reviewing streaming data:

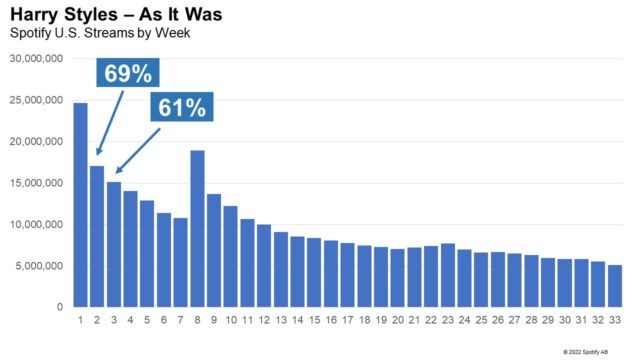

1) How do the song’s streams hold up in the first couple of weeks after debuting? Harry Styles’ fans in the U.S. played “As It Was” on Spotify over 24 million times the week it debuted. As expected, the song got fewer plays in subsequent weeks—but with 17 million streams in its second week, “As It Was” maintained 69% of its weekly plays in week two. In its fifth week, “As It Was” still garnered 12 million streams a week, holding up over half of its weekly streams at its peak.

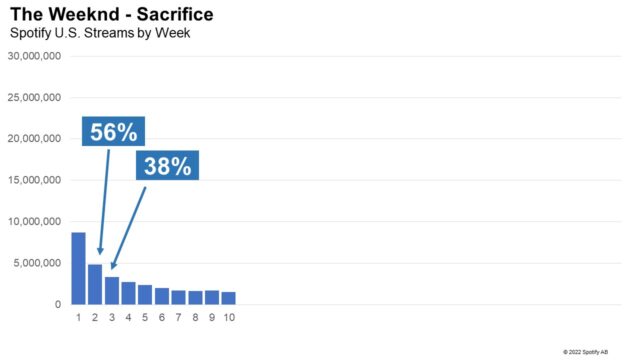

In contrast, The Weeknd’s “Sacrifice” got almost 9 million streams in the week it debuted on Spotify, but users played it less than 5 million times the week after it debuted. Not surprisingly, Integr8 New Music Research clients quickly saw their listeners had little passion for this song.

2) Ignore rank in streaming data. “As it Was” and “Anti-Hero” both debuted as the week’s #1 most streamed song on Spotify. However, so did the Weeknd’s “Sacrifice”, even though it got less than one-third as many plays the week it debuted. A big debut by a major artist such as Drake or Taylor Swift will knock hit songs out of streaming charts’ Top 10, even though those songs saw little erosion in actual plays. Bottom line; look at the raw number of times streaming users play a song from week to week, not changes in chart rank.

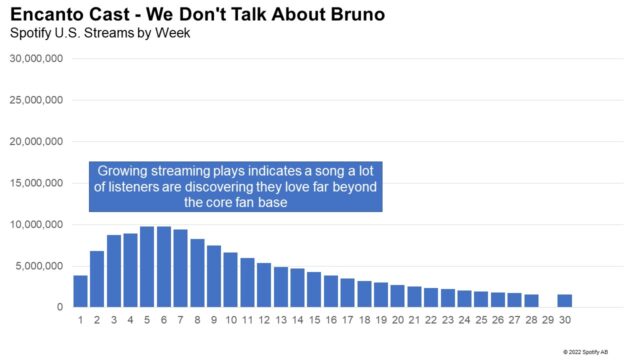

3) Look for songs that are growing week to week. The norm for streaming data is to see big debut weeks. Not all songs work that way. As observed earlier, Lizzo’s “About Damn Time” grew in its first few weeks. As the rare artist whose core fans are older than her casual fans, Lizzo’s “About Damn Time” didn’t see a burst of streaming activity as fans flocked to hear the song right away. Instead, causal fans likely discovered the song on the radio, then went to Spotify to hear it again.

Another example is 2022’s surprise hit “We Don’t Talk About Bruno.” Neither the song nor the movie Encanto were hits when first released in late 2021. But in January 2022, a cold snap and a COVID wave left parents working at home with their kids. Encanto not only came to their rescue to entertain the homebound kids, parents discovered they liked Bruno even after the kids were in bed.

In short, “We Don’t Talk About Bruno” was a song that picked up a much wider fan base than the core Disney fans who played the song when the movie debuted.

Let’s apply these concepts to a song that—as of this writing—is relatively new.

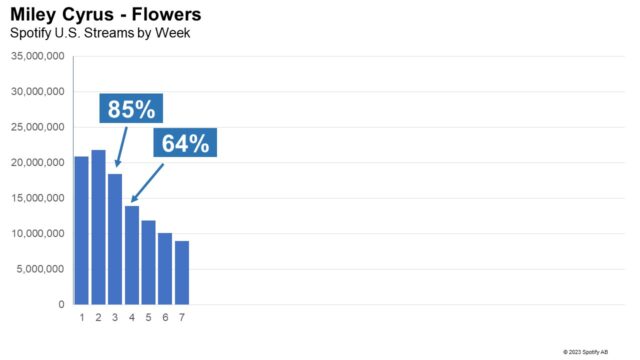

After peaking with almost 22 million streams the week after debuting, Miley Cyrus’ “Flowers” maintained 85% of its weekly plays on Spotify in the U.S. the following week. This pattern suggests—and Integr8 New Music Research clients can confirm—that people are playing “Flowers” because they really like the song, not merely because they’re curious what Miley is up to.

WHAT STREAMING STILL CAN’T TELL YOU

I’ve been urging our clients to use streaming data as one of their new music intelligence tools ever since they were still tracking CD sales. Sadly, many programmers are still hesitant to trust streaming data because its metrics are unfamiliar and confusing. It is my hope that by empowering programmers to understand the story each song’s weekly play counts is telling about each song and its artist, radio programmers can confidently maximize this amazing resource.

However, streaming plays can never tell you everything you need to know about a song to know if your station should play it. It can’t tell you how many listeners know each song, which segment of your audience is most passionate about each song, how many listeners hate a song enough to change stations if you play it, and when listeners are ready for you to move a song to recurrent rotation. For these essential data, high-quality new music research remains the gold standard for selecting songs best aligned with your music strategy.

Want to go deeper? Join Integr8 Research President Matt Bailey for Retention Rate: The Magic New Metric for Measuring Hit Potential in Streaming Data: The Webinar Tuesday, April 19th at 2PM EDT/11 AM PDT.