This is the second in a series about how listeners engage with music across traditional and emerging platforms

Before the advent of callout in the 1970s, radio’s only new music research tool was record sales. When people stopped buying a record, radio stations stopped playing the record. In the 1960s, almost every hit you heard on the radio was less than 12 weeks old.

Today, sales data remain a point of insight decades after newer tools for gauging music’s appeal emerged. Still, clients who rely on our Integr8SM service for insights into their audiences’ responses to new music are often surprised when new songs become top sellers but don’t instantly debut at the top of their new music research that same week.

How do music buying patterns compare with how consumers listen to new music?

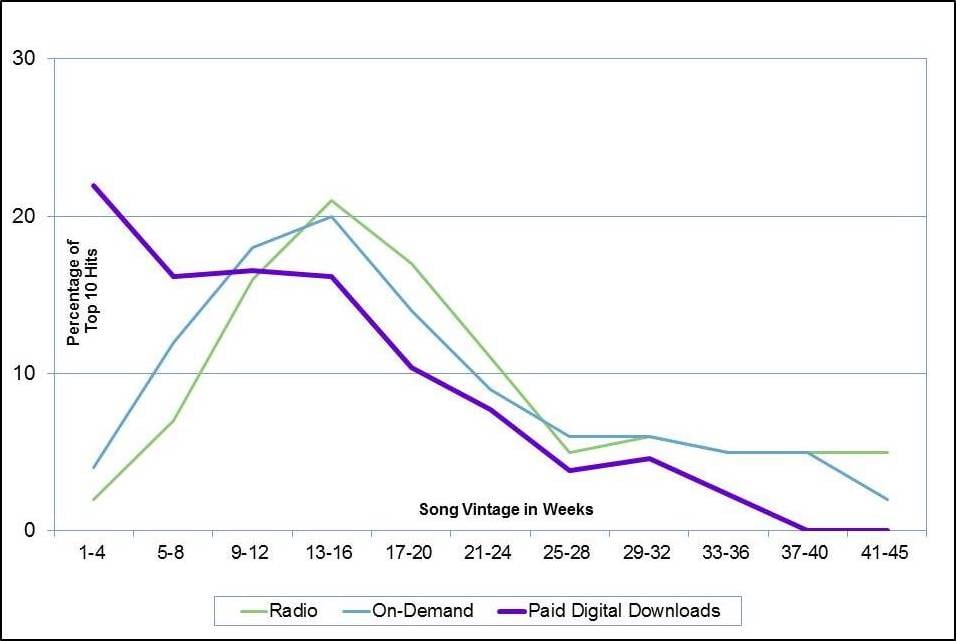

To find out, we analyzed 26 consecutive weeks of the Billboard® Top 10 Digital Songs chart, which ranks the biggest paid digital download singles in online stores such as iTunes. We did the same analysis of Billboard’s Top 10 songs for Radio exposure and On-Demand streaming in each of the same 26 weeks that we compared in our previous post.

The verdict? Music buying and music listening patterns are fundamentally different. When you understand why they’re different, you’ll also understand how making new music decisions based on sales data can lead your station astray.

Digital download sales follow a different pattern than listening behavior (© 2014 Billboard Magazine)

While the majority of songs listeners hear most on the radio and play most on on-demand streaming services (such as Spotify) are between nine and 20 weeks old, the majority of songs listeners buy most are 12 weeks old or less. That’s the same 12-week pattern that drove airplay in the 1960s when Top 40 radio relied on record sales for many of its airplay decisions. Unlike radio exposure and on-demand streaming behavior, digital download sales do not build over time.

So, why are buying and listening patterns so different?

Just because people stop buying a song doesn’t mean people stop playing it. Think about your own music collection. You probably own some songs that you forgot about almost as soon as you got them, just as you probably have songs you’ve listened to regularly for years. When a song’s sales decline, it means fewer new people want to own it. It doesn’t mean the people who already bought it stopped playing it.

If you exposed new music on your radio station solely based on how well the song was selling, you’d play songs most frequently when hardly anyone in your audience knew the song. If you were to stop playing a song as soon as its sales dried up, you’d likely be dropping the song at the moment your audience was most interested in hearing it.

This difference was the first lesson radio learned from the advent of callout in the 1970s.

Since the best-selling songs are significantly newer than the biggest songs on the radio and the songs listeners play most on on-demand services, you might assume you could use today’s song sales to predict tomorrow’s hits on your radio station. In our next installment, we’ll show you why strong debut song sales can lead your station to stiffs—and what to look for in song sales data to avoid those stiffs.

You are absolutely correct regarding new music. My most important category is recent hits. I find that when playing out in public that the most requests I receive are for songs that are 6 to 12 months old… or very popular songs that are up to 10 years old.

I do a lot of Country-Pop events and get the most response from established artists and real hits. I’ll opt to play Garth, Hank, or George Strait before a newer song to get the party going. Works every time before the Electric Slide.

Only a few songs print through. That’s the way it’s been since the 90’s. Just sayin’

Pingback: Wednesday, January 28, 2015 - RadioInfo : RadioInfo

Great insight! PD’s should be very cautious of letting sales and Shazam stats weigh heavily on important music decisions. Been waiting for someone to write this article and back it up with facts.