This is the first in a series about how listeners engage with music across traditional and emerging platforms

For decades, radio has debated the question of how fast stations should move through contemporary music. When modern music research first emerged in the 1970s, radio stations began holding on to hits longer than they did in the 1960s when they realized listeners still loved and listened to songs weeks after they stopped buying the record. Ever since, the question comes up every so often whenever changes in music consumption or audience measurement emerge, such as the advent of PPM® or the emergence of streaming media.

Many of North America’s leading contemporary music stations rely on Coleman Insights for our Integr8SM service, which provides these stations with research on how their target audiences respond to new music. Three questions our Integr8 clients always ask are:

1. How long should I give new songs to catch on with my audience?

2. At what point do new songs reach their peak with typical listeners?

3. At what point should I consider a song no longer a hit, no matter how much listeners still love it?

Does the vintage of the songs radio gives its listeners vary dramatically from the songs music fans play for themselves when they choose to be in control of their own music?

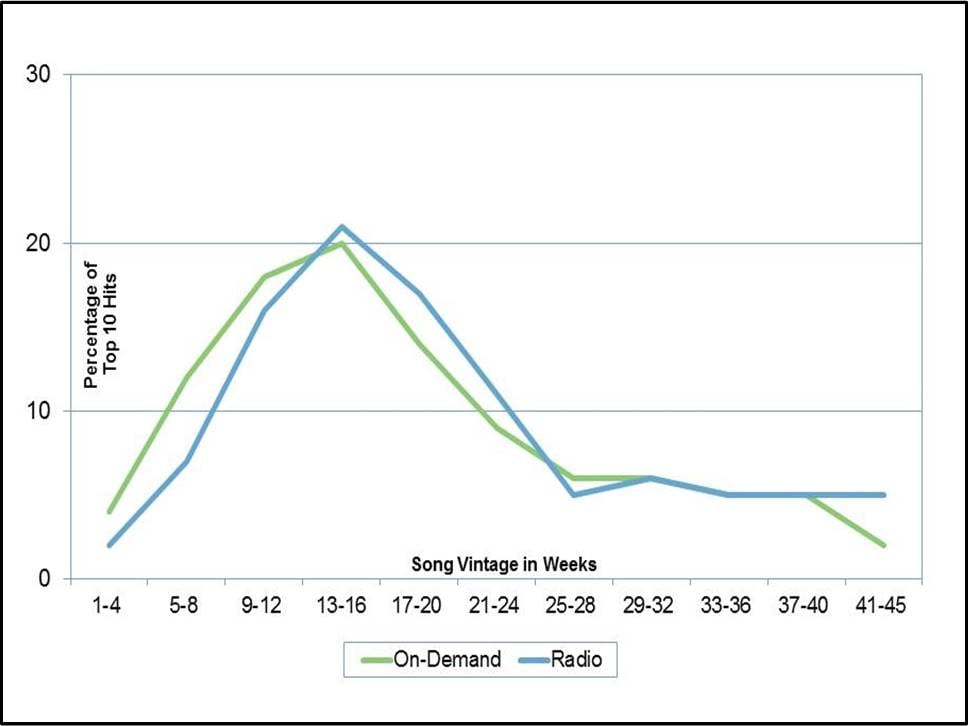

To find out, we analyzed 26 consecutive weeks of Billboard® Top 10 On-Demand Songs (charts that rank the biggest songs of on-demand streaming services such as Spotify) to determine the age of the songs listeners play most when they’re in control of their music. We then pegged each song’s vintage to when it first entered the Billboard Hot 100, so that we can see when each song first entered the public consciousness, not when the record company released it. We then did the same analysis of Billboard Top 10 Radio Songs in each of the same 26 weeks.

The results? The vintage distribution of on-demand’s biggest hits is remarkably similar to the vintage distribution of radio’s biggest hits. On-demand’s curve leads radio’s curve, but the difference is measured in days, not weeks.

Percentage of Top 10 Hits by Vintage in Weeks (Copyright © 2014 Billboard Magazine)

While there are slight variations between on-demand streaming and broadcast radio exposure, a comparable pattern of song development emerges for both media:

1. Songs are typically growing in their first 8 weeks

2. The majority of the biggest songs are between 9 and 20 weeks old

3. Songs are typically in decline after 20 weeks.

Of course, there are variations in the performance of individual songs. As a recently circulated graphic published by Spotify’s Director of Economics highlighted, Meghan Trainor’s “All About That Bass” caught on faster on streaming services in the U.S. than it did on radio. Tove Lo’s “Habits (Stay High)” also broke on Spotify before radio picked it up. Other songs developed faster on radio than on streaming media, such as Maroon 5’s “Maps.” Finally, one particular song, Idina Menzel’s “Let It Go”, was huge on streaming but absent from radio, a fact many Frozen-weary parents appreciate.

Beyond these few notable exceptions, we are struck by just how similarly most of the 45 songs we examined developed on radio and on-demand services. Many of the songs that radio programmers thought would never go away, such as OneRepublic’s “Counting Stars,” Katy Perry’s “Dark Horse” and John Legend’s “All Of Me,” were the very same songs listeners continued to play for weeks on the on-demand platforms long after the typical expiration date.

In upcoming installments, we’ll show why music purchasing habits follow a fundamentally different pattern than music listening behavior, plus we’ll examine how Shazam fits into this picture.

Pingback: Podcast Interview: Warren Kurtzman of Coleman Insights