The following blog was written this past February and was originally scheduled for publication in March. After COVID-19 hit, our Tuesdays With Coleman blogs shifted to content focused on the crisis. When most stores were forced to close due to the pandemic, I wondered if this blog would come across as insensitive and untimely.

Ultimately I decided to run it because a) branding challenges are evergreen, whether the country is in a pandemic or not; b) it serves as something of a time capsule, me taking notes in a store without wearing a mask or fear of catching something.

I was beer shopping with my friend Andy recently when he stopped and stared back and forth at two packages at the shelf. “I’m no branding expert,” he said. “But this is weird.”

These were the two packages he was looking at:

“They both say Fat Tire, but only one is Fat Tire. The yellow one is a completely different beer.”

Indeed it is. One is the original Fat Tire, an amber-colored malty ale launched in 1991. The other, a Belgian wheat, is a completely different style, gold colored and citrusy.

I really like New Belgium Brewing beers and they generally come with their own unique names. But in this case, the brewery went with a line extension of the flagship Fat Tire brand.

According to marketing strategist Al Ries, “Line extension is a loser’s game. It doesn’t usually work, but even if it does, it almost always damage the core brand.”

There was that time recently when my wife and I popped into Macy’s, and saw the signs for “Macy’s Backstage.”

The idea of a department store having its own lower-priced outlet is not unusual in and of itself.

There’s Saks Off 5th, Nordstrom Rack, REI Garage and Gap Factory to name a few. But Macy’s Backstage isn’t in an outlet mall, or even another location. It’s inside Macy’s! The real Macy’s is on the other side of that mirror!

A few things happened in my brand perception of Macy’s that day.

I was distracted from the Macy’s shopping experience. Rather than search through Macy’s for deals, I got lost in “Backstage” looking for deals. Once I ventured to the other side of the mirror, I found myself comparing Macy’s prices against themselves, because some similar products were priced drastically different–in the same store! And Macy’s Backstage didn’t always have the best deal.

The checkout aisle was loaded with things like a vending machine, candy and stuffed animals. Is this Marshall’s or Macy’s?

On a clearance rack, I found:

- A heated steering wheel cover;

- Kenneth Cole underwear;

- A Bubba Gump Shrimp Co. hat;

- A resistance band;

- Two Nike wallets.

This looks like something I might find at Kohl’s, but I just have a hunch like they might separate underwear, a wheel cover and a resistance band into different sections.

And I definitely would not have expected to find a Bubba Gump hat and wheel cover at Macy’s.

But, you may say, this is Macy’s Backstage, not Macy’s!

Therein lies one of the dangers of line extension. I’m going to mentally associate the two because they share the name. The fact that the two stores are literally in the same space only exacerbates the association.

Let’s say you walk into Nordstrom Rack and find some good deals but still determine the clothes are Nordstrom-level quality. Your perception of the Nordstrom brand is likely not eroded.

Would the same be true if you found Nordstrom Rack loaded with Jordache, Fruit-of-the-Loom and Bubba Gump hats?

It would not.

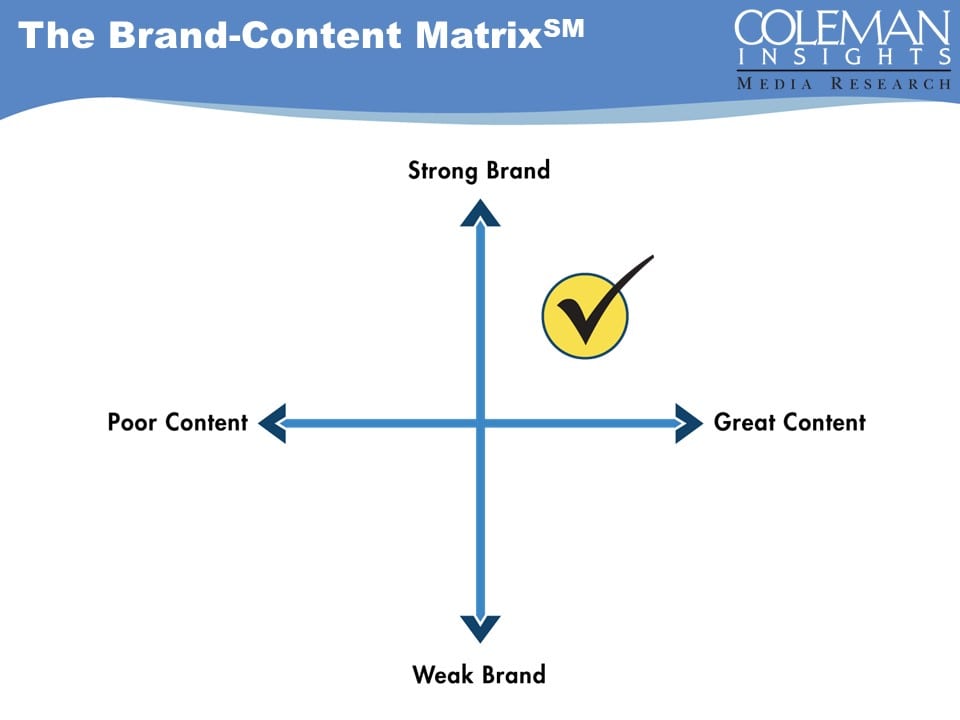

The point is, you must treat your brand with delicate care. Brand erosion is generally a slow process that is hard to come back from and opens up opportunities for focused competitors. It’s also why tracking your brand in perceptual research is so important.

Even Bubba Gump knows the power of brand focus. Sure, he serves a lot of different styles in many different ways.

But, you know what? It’s all shrimp.