The 2024 film “A Complete Unknown” uses Bob Dylan’s electric controversy as a lens to examine a timeless business dilemma: how do established brands navigate radical change? While on its surface it’s a Bob Dylan biopic chronicling his journey from folk darling to electric revolutionary, the film offers real insights into every business’s challenges when disruption comes knocking.

Photo credit: Gennaro Leonardi / Shutterstock.com

Picture New York, 1961: A young Dylan arrives with nothing but a guitar and raw ambition. The folk establishment—Pete Seeger, Woody Guthrie, and their circle—embrace him as their heir apparent. Dylan becomes folk music’s golden child, selling out festivals and earning acclaim as the voice of a generation. But beneath the surface, a transformation is brewing.

The film captures Dylan’s growing fascination with electric music’s raw power and possibility. This wasn’t just about amplification – it was about dramatic change. As Dylan begins incorporating electric elements and pushing beyond traditional folk boundaries, the pushback is immediate and fierce. His artistic metamorphosis becomes a case study in brand reinvention.

The pivotal moment arrives at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival. In what would become one of music’s most iconic crossroads, Johnny Cash gives Dylan succinct advice about innovation: “Bob, track some mud on the carpet.” It’s a perfect metaphor for disruptive change. Sometimes you must make a mess to progress.

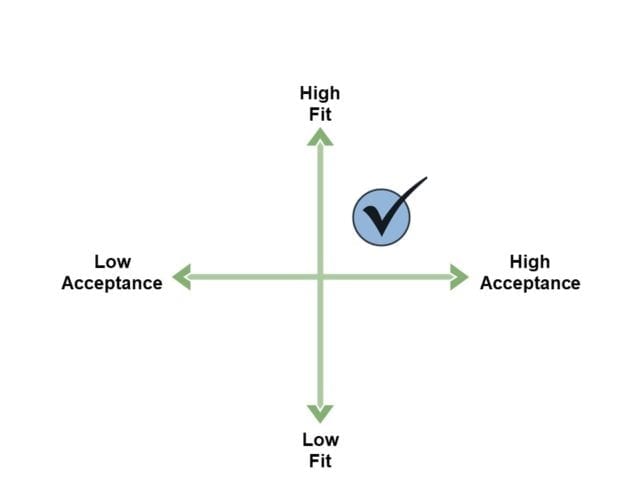

What follows is electric music history: Dylan plugs in at Newport and launches into “Maggie’s Farm” and “Like a Rolling Stone.” The audience’s reaction is visceral. Shoes and garbage hurled at the stage, boos drowning out the music. Today’s market research equivalent would be a sea of “hate it” ratings. Yet, amid the chaos, there were cheers too—the early adopters who recognized the future when they heard it. It requires skill and strategy to identify when “hate it” is masking an underlying dramatic and meaningful change. Not every new thing meets that criterion. Dylan’s strategy was change. The folk industry wanted none of it.

Photo credit: Derick P. Hudson / Shutterstock.com

The film’s genius lies in showing how time validated Dylan’s gamble. While folk purists’ influence waned, Dylan’s new electric sound captured a growing audience, proving that sometimes the path to longevity requires abandoning the very thing that brought you success.

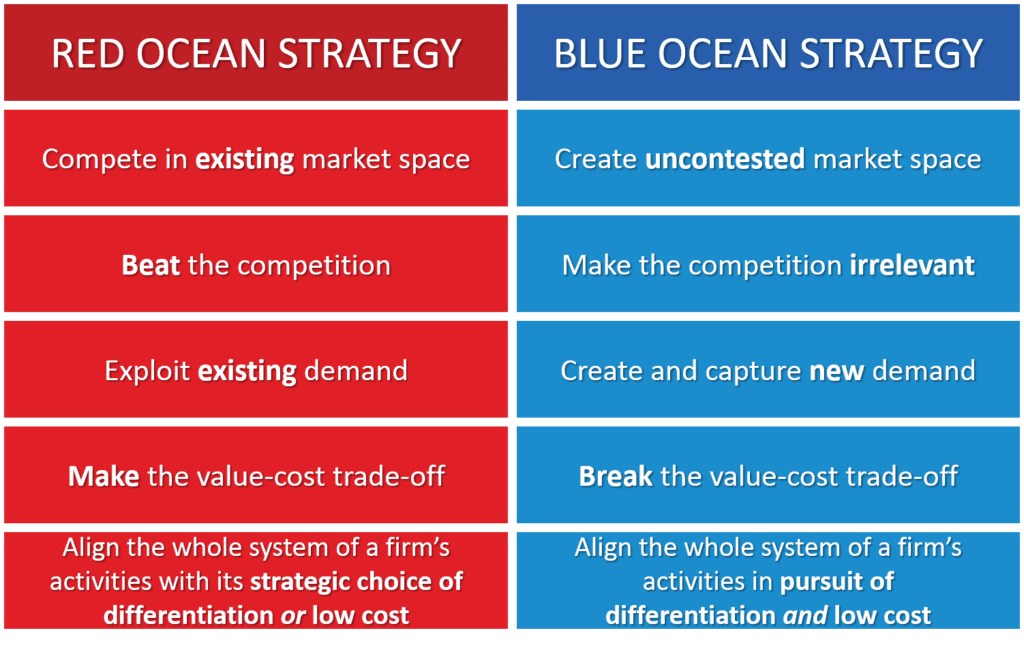

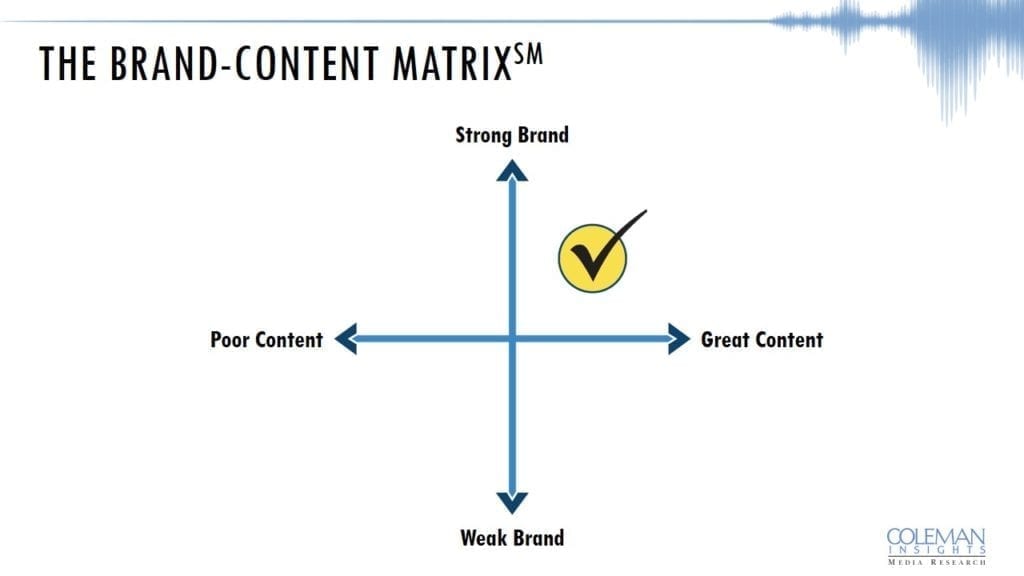

This historical moment offers a powerful framework for analyzing today’s radio industry. As streaming services, podcasts, and digital platforms reshape audio consumption, radio stands at its own Newport moment. Should it cling to traditional formats that still command loyal but shrinking audiences? Or should it seek its own “electric” revolution?

The question is not simply whether to change, but how to evolve while maintaining core values. Dylan didn’t abandon storytelling or social commentary when he went electric—he amplified these elements through a new medium. Similarly, radio’s challenge is not about abandoning its strengths but in reimagining how its strengths can be expressed in an evolving media landscape.

What makes this narrative particularly relevant is how it illuminates the universal challenge of brand evolution. Whether you’re a musician, a radio station, or any business facing disruption, the core question remains the same: Will you throw shoes at change, or will you “track some mud on the carpet?”