In our research, when we ask podcast consumers which categories they’re interested in, Music is regularly in the top 10. And yet, there are no music podcasts at the top of the podcast charts.

Why is that?

One obvious reason is that most podcasts don’t actually play any popular music for various reasons, but it likely mostly stems from a fear of getting sued.

Back in March, I met Peter Ferioli and Christian Swain, co-founders of Pantheon Media, a network that features music and sports podcasts. I’ve long been fascinated by this conundrum, and it has led to several discussions as to why this is the case, what might be done to solve the problem, and how research can play a role.

Peter, Christian, and I spoke at length on this topic for this special edition of Tuesdays With Coleman. The structure for rights fees in place for radio and streaming doesn’t apply to podcasts, and you’ll learn why as Peter and Christian lay out a vision of how a new system might work. They also explain how “fair use” works and why it allows them to feature popular music in their shows.

As a bonus, you may hear the term “Gordian Knot” referred to in a conversation for the first time in your life.

Here’s my conversation with Peter and Christian, with the full transcript below:

Jay Nachlis (00:00)

I ‘m Jay Nachlis from Coleman Insights and joining me from Pantheon Media today are Peter and Christian. ⁓ Guys, thanks so much for joining us for this discussion. It’s great to have you.

Christian Swain (00:11)

Thanks for having us, Jay.

Peter Ferioli (00:12)

Pleasure to be here, Jay.

Jay Nachlis (00:14)

So Pantheon is a network with music and sports podcasts, including the official Metallica, the Mighty Metallica is on your roster. you know, we met in March, I think, at the Podcast Movement Evolutions Conference. you know, we have this shared love of, you know, we’re all music geeks and have this shared love of music. We love music podcasts. And it’s, I guess, it’s kind of…spun into several conversations about the topic of using music in podcasts, which has always been fascinating to me. And I think it’s a topic that maybe hasn’t been talked about enough. And there’s a lot of, I mean, you think of things that have misunderstandings, misinterpretations, this has gotta be like right towards the top of the list, right?

Christian Swain (01:01)

True. Well, I think it all starts with, you know, the working with an industry where there is a bit of a Gordian knot when it comes to licensing and maybe that needs a, you know, a refresher into the 21st century on what that could mean and how the ⁓ economics work when spread.

you know, by the smaller creators that there is a lot of upside to them if they would pay attention.

Peter Ferioli (01:33)

So let me break that down into the layman’s terms those of you who don’t know what a Gordian knot is. ⁓ what I think, what Christian was putting it in the terms of some of the different types of music licenses that podcasters would actually need today to actually use a track, you would first need.

Christian Swain (01:39)

What? We gotta start with Greek history? Well, come on, everybody should know that. Classically trained.

Jay Nachlis (01:40)

What?

Christian Swain (01:54)

Yeah, yeah.

Peter Ferioli (01:59)

It’s two different sets of licensing and buckets this falls under. The first set are the master recording rights. And that’s the actual recorded version of the song that actually is usually owned by the label. Right. And then you have the composition rights, which are the like the melody, the lyrics, and those are typically owned by the publisher. Right. Right. Then, OK, so here’s where the problem becomes for podcasters. OK. And it gets really hairy, and hence the Gordian knot.

Christian Swain (02:19)

The songwriters.

Jay Nachlis (02:21)

Okay.

Peter Ferioli (02:29)

You don’t just deal with these PROs like radio or performance rights because podcasts are actually considered on demand and downloadable because of the RSS feed and the technology that podcasting originally stemmed out of that doesn’t today still define podcasting but is a major infrastructure behind how podcasts are served and delivered to you via Apple, Amazon, Spotify, etc.

Peter Ferioli (02:58)

So you have these other set of rights. You need reproduction rights to copy this music into your show, right? Then you have to have distribution rights to get it out to all the listeners from your RSS feed, wherever it’s being stored and served to everyone listening. And lastly, you have something called digital transmission rights, right? And those are for streaming purposes. So now you’re looking at six different parties to just use 30 seconds when all you want to do is try to promote and sell and push music discovery at heart in that 30 seconds of music.

Christian Swain (03:36)

Yeah, we understand why, you you can’t just make a podcast and start playing songs. That’s not the point. And that’s not what we do. You know, we are, you know, we kind of consider ourselves like the modern version of Rolling Stone magazine. You know, we’re audio and video. But the thing is, is that we need to talk about the music by showing the example. Now we try to keep the the samples short and in context.

which does fall under fair use. So we are covered, but we would love to figure out a scheme that allows licensing, full licensing to be used so that more people would engage in this activity and provide more marketing opportunities for those rights holders as an end result.

Jay Nachlis (04:23)

Yeah, so let’s talk about fair use for a second and what exactly that means based on, so it sounds like there’s a journalistic component to it, right? When you mentioned Rolling Stone as an example, so it’s like, is the difference that if I’m covering it in that way compared to, I don’t know, just playing it as part of the best of the 2000s playlist that I put together, is that the difference?

Peter Ferioli (04:47)

I’m gonna start on this one just because I would consider myself an expert in this because, you know, we’ve been doing this for 10 years and about a year ago, Warner Brothers and Universal en masse decided to flip on a switch in Spotify that basically gave us, I believe over one week we received 4,700 individual notices that basically took us through a three page multi-tier process that fair use was one of the main cruxes of it. And so I’ll tell you a little bit about that and that experience is this. Fair use is, it’s a legal doctrine that is used in defense. It’s not a right. You can’t claim it on the front of things.

And it’s defined when you use copyrighted material for things like criticism, comment, news reporting, parody, teaching, research, pastiche. There’s different, a lot of different things that it covers when you use ⁓ some of copyrighted material. But then the four factors, if it were ever to come to a court case where you did go to trial and during the trial, your lawyer claims for fair use.

Christian Swain (05:46)

Parody.

Peter Ferioli (06:07)

The judge and the juror, if there was a jury, which most likely would never be, but the judge would look at four main factors around what is considered fair use. The number one, it’s the, you know, it’s the purpose of the use, right? The nature of the works, the amount of it used and the effect on the market for the original. Did it damage it? Did it lift it up? What did it do to it? Did it take?

Money away from it. How did it impact the market when this happened, right? So if you’re using a clip like we do for review or critique or demonstration, that is covered under fair use. Should it get to that point of when we were, and we are very confident in that. But if we simply take 30 seconds of our favorite song and use it as background music, use it as entertainment purposes, just an intro on something that doesn’t apply,

Christian Swain (06:51)

If it ever got to that point.

Peter Ferioli (07:05)

That almost would never qualify.

Christian Swain (07:07)

Don’t use Kenny Rogers the Gambler for a gambling podcast.

Jay Nachlis (07:11)

Right. Right.

Peter Ferioli (07:11)

So at the end result, basically, what you’ll get from an attorney is never do it because it’s expensive to defend should it get to this point, right? Not all of them have the network, the ways and means and the experience and wisdom that we do having as many podcasts as we do and understanding the differences and what we’re doing, right? A lot of podcasts are just not worth the risk to an individual podcaster at the end of the day.

Jay Nachlis (07:38)

Okay, now I’m curious about how hosting platforms play a role in this and to, I guess to explain to everyone what that is. If I’m an independent podcaster and I want to get my podcast out to the world.

onto all the different platforms, Apple and Spotify, et cetera. ⁓ Like you mentioned before, there’s an RSS feed. And that’s when you go to a podcast hosting platform, some examples are like Buzzsprout and Libsyn and Blubrry They will take that and they will put your show notes in there, right? You upload your episode and it goes out to the world. So do they have any sort of role in this or no?

Christian Swain (08:08)

distributed out.

Peter Ferioli (08:19)

I’ll take a first shot then I’ll let Christian talk. this one’s interesting because right now, yeah, well, and right now, you know, none of these hosting platforms. So what you’re talking about, Jay, is where when I make a podcast, I make an audio file, I have to put it up somewhere so that it can be distributed and heard everywhere. Now, originally, none of those places in the podcasting industry for the first 15 years were also places that…

Christian Swain (08:20)

Yeah, go ahead.

They know about it, yeah.

Peter Ferioli (08:46)

Also had blanket music licenses. So we have a world now where that you have some of these hosting services That you know do have a comprehensive blanket license for their platform So like a spotify for podcasters or an anchor or literally amazon music, right? So when they make their originals, they don’t have to negotiate in the same way that the independent podcaster does but these host services at the end of their day are just, you know, what we would say are CYA, which is cover your ass. And it’s about liability, right? So if you have one second of any copyrighted music on a show on one of your hosts, like a Libsyn or a Blubrry or anywhere else, and they are contacted by the rights holder to ask that it gets taken down, they are liable. So ultimately your host is who is responsible for the distribution of copyrighted material. And none of them want to take on the liability on behalf of thousands of individual creators who don’t know their intentions.

Jay Nachlis (09:53)

Right, yeah, that makes sense.

Christian Swain (09:55)

So none of those companies are willing to, you know, be the the the law enforcement of ⁓ of usage out there. We’ve presented some concepts that we might be willing to, ⁓ you know, take that role on or basically somebody would have to take that role on if, you know, it was strictly a downstream, you know, Hoover up. the nickels, make sure that they’re using it properly and provide reporting and monthly checks to the rights holders.

Peter Ferioli (10:32)

And what Christian’s talking about was deployed in the best way, the best example we have of what Christian is talking about is content ID on YouTube. And so when we talk about the world’s top premier kind of copyright material filtering platform right now that notifies rights holders in near real time about their usage of via a creator or influencer. And nowadays, especially, we’re in this weird world where videos are podcasting, live streamers are podcasters, Spotify’s got video for podcasters. And the more that they are using music and being flagged, but they are given the opportunity because of the ubiquitous nature of where all video is being kind of served through.

Christian Swain (11:09)

Yeah.

just on YouTube, right?

Peter Ferioli (11:25)

You know, just do YouTube. you know, obviously every different, we talk about the hosting platforms and 60, 70 from places your podcast can be found as an audio format. Well, there’s only one or two right now that you’re going to find them in video and they really can, can, can control that. And they have a great system there. So they do, they do allow the usage of copyrighted works on YouTube. You can either share in the data.

You can share in the monies, you can be blocked in certain countries, or you can go through a multi-page process of claiming fair use by which many of the large folks who have the five, eight, 10 million listeners on YouTube that are doing music reviews and critiques, Rick Beato, ⁓ a couple other ones that we know, are dealing with this issue right now where they’re getting copyright strikes where they used to just be able to claim fair use.

Christian Swain (12:17)

It seems like YouTube has gotten a little more militant on the usage, ⁓ certainly with certain artists. But at the same time, you’ve seen just like ⁓ when ⁓ digital music began ⁓ with Napster, there was this Heisman of, ⁓ no, we’re not gonna do this. And eventually everybody went along with the program.

Christian Swain (12:44)

And so it’s just a question of how long do you have to put up with that before everybody sees the long-term benefits? And this has happened in the recording industry time and time again. They always fear the technology. And when they finally employ that technology, they end up making more money than they ever did before.

Jay Nachlis (13:05)

Right. So when you think about the way that labels look at this, it, ⁓ is a lot of it from being antiquated, like an antiquated view of it?

Christian Swain (13:17)

I did use the term Gordian Knot.

Jay Nachlis (13:20)

Yes, you did. Yes.

Peter Ferioli (13:20)

Yeah, the labels, listen, at the end of the day, there’s only one thing the labels care about, which is money. Okay, so if you go back to it, what is their answer is this, is if there was a there there, they would have a system in place. And what do we mean by that? If you look at the company pex.com, which became rights.com and some of the data indexing they did in their studies of kind of analyzing all… Yeah, they analyzed all… They analyzed a massive amount of YouTube. They indexed actually every podcast out of 200.5 million of them. They ran through a filter and they identified music usage in both YouTube and in audio podcasting. What they found was in YouTube, you had about 83 % of videos were using music of some form or another copyrighted license, etc.

Christian Swain (13:49)

trying to copy YouTube’s content ID. using music.

Peter Ferioli (14:15)

And then in audio podcasts, and they found that only 17 % were using music. And this was probably about five years ago. That’s probably adjusted a few points upward. But at the end of the day, there’s an opportunity there to use more music and grow. But conversely, if we look at the top 200 podcasts that are…taking all the dollars and ad dollars and taking all the listeners, right? How many of them are using music or went out and paid sync rights to use a track or use it? None of them are. So you have the music labels going, look at all the top podcasts. None of them are music. None of them are using music. There’s no money in us licensing any of these top people because so that’s where we came in years ago with an idea that we called AMP, which was the Alliance of Music Podcasters in our early days where one of the solutions we thought and we still believe was

Christian Swain (14:42)

are not exactly music podcasts, right?

Peter Ferioli (15:08)

If we could aggregate our entire vertical of not just Pantheon and our hundred plus music podcast, but then some of the other music podcasters and networks out there that we could create a set of data and create a blanket license that we could then go to the labels and get. But the issue still becomes at the host level and the data and tracking and getting the hosts, these hosts companies to have some skin in the game at some why financially should they get in the business of tracking this these data and stats on their end for these labels? Right? Spotify did it because they went negotiated and got sound exchange and they could come all the force to bear with their subscription product. But what is in Libsyn and Blubrry and Art 19, What is in their interest for the labels to go, hey, every month, here’s all the data and all the music usage that was happened on on the platforms, right?

And so that’s where we’re at. know, there’s got to be money there for somebody and the labels don’t think there’s money there. It being a lot of money right now.

Jay Nachlis (16:12)

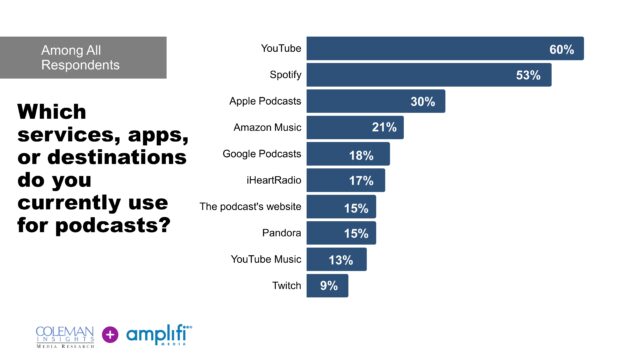

That’s really interesting. It’s interesting what you say about the top podcasts and them not using music and that argument, right? Because a lot of it comes from, like when we do research, we did the state of video podcasting study back in March that we presented at that conference we were talking about. And it’s very typical when you do these types of industry studies and you’re just researching the podcast consumer and you’re asking them about category fandom, not actual usage, but you ask them what categories are the most into. Music is always high.

And the last one that we did, was number seven overall. That’s really, really big. And so there is a gap between people’s perception of, hey, I love this, I want this type of podcast and their actual consumption. But it comes from what you’re talking about. It’s because there’s not enough popular music. I was recently reading about Song Exploder, which is a really big podcast, right? Where artists come on and they dissect a song and how was it made? They get in the weeds, it’s great.

Christian Swain (17:00)

Yep. Been around for a long time.

Jay Nachlis (17:08)

And the creator was talking about how, I don’t remember if it came off for a while, but the whole point was at one point he just couldn’t afford all of the fees. And I guess it became big enough that they were able to do it. that’s the quandary, right? It’s not that the popularity isn’t there. It’s not that you wouldn’t have better performing music podcasts if more were able to be used, right? So, yeah.

Christian Swain (17:35)

There should be. You know, we have been told time and time again that in the music industry, we are the marketing arm nowadays. The old ways of trying to get people to pay attention to new music was through the FM DJ, the record store clerk, and the music press. None of those exist anymore. So we are the 21st century version of all those things wrapped up into a single platform.

And we think that the music industry should lean into us and duplicate more of us ⁓ by allowing a licensing scheme that would be conducive to that sort of growth.

Jay Nachlis (18:22)

Yeah, I think the condemnation of FM radio as the lack of source of music discovery was a little too much on the one side, but your point is well taken. It’s a lot less than it was for sure. And people are going to streaming for music discovery in droves and it should be a conduit for that. That’s not happening, yes.

Christian Swain (18:29)

Yeah, you also have a much larger pool of music to choose from out there. So how do you find what is the next thing that you want to hear? We know that algorithms and playlists aren’t exactly the best way to do that. Music is a very, very personal experience. so word of mouth is actually the best way that most people have discovered new music. So, the algorithm will feed you, you know, your commonalities, as we like to say, you you know, if you’re a fan of Black Sabbath, well, geez, they think you’re going to be a fan of Ozzy Osborne. Well, yeah, no kidding. ⁓ But, you know, what, you know, that’s not how people actually consume music. They want to explore. They want to put their fingers out into other potential possibilities, whether they like it or not. ⁓ And if you had you know, a system to help recommend those sort of things, that would be better for everybody.

Jay Nachlis (19:41)

I think a couple of analogies would be thinking about ⁓ even like host read ads, for example, are always more effective than, Yeah, right. Why? Because it’s someone you trust telling you something. It’s a recommendation. much, it’s just, it’s more personal than an algorithm, right? ⁓ And I think that that, and same thing, like the way people discover new podcasts for years, in fact, up until this year, the number one was always friends and family.

Christian Swain (19:50)

Yeah, and the dynamic insertions. Yeah.

Jay Nachlis (20:12)

Now social media is number one. Friends and family is still up there, ultimately it’s work, to your point, it’s word of mouth. And so we’ve talked about when it comes to a solution and how do we convince the labels? How do we get them to a point where we can get to the system you’re talking about where every independent podcaster could have the opportunity to use popular music? How do we convince them? What’s the, you know, what do we do here?

Christian Swain (20:34)

We dangle a big dollar in front of them. That’s how we do it. That’s what they want, definitely.

Peter Ferioli (20:41)

Yeah, yeah, they have to understand that it’s definitely a marketing music discovery, you know, in the catalog, back catalog exposure is where it’s, you know, it’s really important. How do you, if you have a friend or you get a recommendation from somebody for restaurant, do you trust them if they haven’t eaten there? I mean, you let’s talk, I heard about this song on this podcast. They talked about it, but I didn’t hear it. You should go check this band out because they just talked about the song, you know, really? That’s how you’re going to recommend or refer something because

Christian Swain (20:58)

Yeah, exactly. But I can’t really talk about it.

Peter Ferioli (21:11)

a friend, you know, read the review of the restaurant, you should go there. Well, did you eat there? Like I wouldn’t trust anybody who’d recommended abandon me if they didn’t hear the band or the song.

Christian Swain (21:21)

Yeah, that makes no sense at all. you know, to talk again in context, we’re not suggesting that they just like willy-nilly let people use music to their heart’s desire. We’re suggesting to put, you know, some rules around it. And that is basically the fair use rules, you know, parody, you know, commentary, education. Those are things that I think benefit from small samples of the music to express what it is that you’re talking about so that the concepts and ideas get fully realized to the audience.

Peter Ferioli (21:58)

Now, let’s just say that we are allowed to do that though, actually. Those 4,500 notices we got, we went through the three phase step, declared fair use. When you come through Spotify, they gave you a notice. There was four things. You can say, this is not in my work. We have rights to use it from the rights holder. We’re using it under fair use or we will remove it. You have to check four actions and then they check back and then they take it down if you haven’t responded and you get like, you know, I think it’s 72 hours, three days to respond to these notices. If you don’t, they take your song, your podcast down off Spotify. So we did 4,500 and all of them, we did fair use on all of them. Every one of those episodes is still up on Spotify. So if we were to go in front of a court today or a lawyer, I’d go, I have 4,500 cases of it being accepted as fair use and being played on Spotify after we submitted. So, but that’s the problem. They would still go after and shut your account down and you kind of never get to that point. So we’re not, you know, we, you know, we advocate poking the bear a little bit if you claim fair use and no one has ever been sued in the history of the internet for using a piece of music in something in a creative social work ever.

You can never find, as a matter of fact, only one person was ever sued or attempted to be sued in the Napster years for uploading and sharing a music file at all. Because all the liability, it’s all cover your ass. It’s a whack-a-mole game, Jay. If Podbean gets a notice from Universal because somebody’s putting up their entire Beatles catalog as podcasts, right? And people can do that. Anybody can do that today. You can go make a podcast and put up your entire music catalog, right? And see what happens, okay? Right away, the… Right.

Christian Swain (23:37)

We don’t recommend that.

Christian Swain (23:43)

Definitely don’t recommend that.

Peter Ferioli (23:45)

The technology exists that it can be tracked. The rights holder can get notice in real time. You can get the data in real time if everybody’s listened to it and you can share in the monetization of it. So if YouTube can do it with Content ID, the question becomes, why can’t the rest of them do it? So, right, and they can, especially in today’s AI filtering world, they can. Do they want to? Is there money in it for them? Right, that’s now the next thing because Google has AdWords. So it’s in their best interest to make a song

Christian Swain (23:47)

Okay. Yep.

Peter Ferioli (24:15)

Like, ⁓ let’s take one for example, ⁓ the kids, the African American kids were listening to Phil Collins In the Air Tonight. So there’s a reaction video, right? Before that, you know, they let that go because that song blew up and made more copies and sold more streams and listens in the next two weeks than ever. So at least that they understood in the moment they could go from zero to a hundred million overnight of views because they let it go as the rights holders. They could have said, no.

Jay Nachlis (24:22)

Yeah, yeah.

Peter Ferioli (24:42)

And squash that in the first one minute when they got the notification, right? But because there was a system in place to let them share the data, the money and everything and Google wanted to make money on it too, right? So, and then that’s, I’ll end it with this. The dirty secret is that Spotify has, you know, millions of uses of full songs in their music category under their podcasting. And none of it is being paid back to the rights holders right now.

But Spotify is running ads on those podcasts and making money on all the ads, on all the music, on all those podcasts. Spotify is making money, right? But on the other side of the house, on the same platform, they have SoundExchange paying out for a stream from that song. So you ask yourself, they can track it and they do on their platform. Why not just track the usage on the podcast and pay the rights holder via SoundExchange?

Jay Nachlis (25:17)

Mmm.

Peter Ferioli (25:38)

because then they’d have to start to reveal the ad dollars and what they’re really, what they’re monetizing on the podcasting side of the house to the music people. Do you think they want to do that?

Jay Nachlis (25:49)

Right, right.

you think it, I mean, it obviously comes down to money. is it gonna be, they see that allowing this in podcasts is going to result in more concert tickets sold, more streams of their artists, more merchandise sold, et cetera, I mean, is that, do you think ultimately that’s what’s gonna flip the switch for them?

Christian Swain (26:13)

I think in the end, they’re going to come to embrace just the fact that there is something out there that is ⁓ marketing their wares in a manner that they’re familiar with. So I think that will happen. we would like to just see more folks get in this game and we think that a lot of people are holding back because they’re afraid of that. I mean, for years we were always like, you guys, you can’t do that. And we were like, no, we think we can. we, look, we got some legal ⁓ advice early on that we were standing on some fair use ground. And as long as we maintained that, you know, that you know, education commentary primarily, we do some parody, but not a lot, ⁓ that, you know, we’d be in a good spot. And the evidence is beared out. We have not been shut down. We have not been sued. We haven’t ⁓ lost a single episode.

Peter Ferioli (27:19)

And, you what I would say is that research is absolutely critical and something we are trying to be more heavily invested in here with our creators, what’s the music usage in our shows. And we need data on a lot of these usage patterns, right? So how much music do these podcasters want to use, you know, for how long?

Christian Swain (27:24)

Yeah.

Peter Ferioli (27:41)

And we want to help try to build these licensing models and be transparent with the industry. So with that though, we need audience research, right? To demonstrate the value proposition to these rights holders. So we can show things like, yeah, a podcast listener that’s 40 % more likely to be a music super fan and maybe 70 % more likely to attend a concert. And then that changes what you’re saying, which is, and what we’re talking about, which is the conversation from how do we protect this content to you know, how do we reach these valuable fans with this content, right? So we can flip it on them a little bit. And then with that research, I hope we get the, you know, then some economic modeling, right? So understanding what can these podcasters afford to pay, what rights holders, you know, want and need to make this work for everyone, because we’re not radio stations. There’s a lot of individuals who want to license this right. So it’s not being licensed at one big scale. So

Christian Swain (28:33)

Well, micro radio stations, but…

Peter Ferioli (28:39)

You know, we really, believe again that it’s a problem that has an opportunity to be solved that can benefit the whole ecosystem.

Jay Nachlis (28:47)

Do you envision when this all shakes out, how do you envision this for, what’s the perfect scenario for the podcaster? is it something that, it feels like it’s hard not to be complicated, right? Because there’s so many different levels of whether or not I’ve got a big audience or a small audience, how many songs am I using, how much of the song am I using, right? So how does this look at the end to you guys?

Christian Swain (29:09)

Well, the mechanics are one thing of figuring out like 30 seconds, 10 seconds. I mean, we’ve looked at maybe microcharging of like, if you use 10 seconds, there’s X, if you use 20 seconds, it’s Y, if you use 30 seconds, it’s Z. We’ve looked at that sort of concept. And then the size of audience, I think, is critical. I mean, if you’ve got 100 people,

They can’t be charging you $10,000 for a sync license. You know, it’s like, it needs to be commensurate to the size of the audience. I think more than anything else, you know, so it’s a scale, you know, if you’ve got a hundred thousand people listening to your thing and are all getting excited, well, then you should pay more to use the license, the music, than somebody who’s got a hundred people, you know.

Peter Ferioli (29:56)

So the implementation is actually much easier than we all think. And it’s actually not as complicated, Jay, because all the hosting platforms, almost all of them, they charge a fee. You give them your credit card to upload your file, right? you pay a monthly fee. OK, so now when I go on to, let’s just use Libsyn as an example, because I love you, Libsyn. When you upload a show to Libsyn, you check out

To be a podcast, is this statement not true or is this true or false? You must be in a category to be distributed as a podcast in an RSS feed. Correct, right? So we have this qualifier that you now have to check you’re in the music category. Only the people who check. There’s only four available music categories. There’s music, music interviews, music history, music commentary. Those are the only four available that you can flag yourself as in the podcasting ecosystem. If you’re within those,

Christian Swain (30:31)

True.

Peter Ferioli (30:50)

Your RSS feed gets run through the AI music filter. And then through the AI music filter on Libsyn, I get dinged 0.0005 cents, whatever the streaming rate is for, or the play rate is for a song. If I have a hundred plays of it, if I have 10,000 plays or a million plays, my credit card on file gets billed for that. And I click, okay, I would like to opt in to…

My show being tracked in the music category and pay for the usage of music rights, right? And then that RSS feed goes back to the rights publisher owner. They can listen to the podcast just like they do on YouTube. And in real time, their army of 5,000 people in Germany working 24 seven, checking rights on YouTube to clear them all the time can do the same thing for the other platforms, right?

It’s just, it’s not that hard. It’s why would Libsyn take the time to implement this tech on their side if 10 people are going to use it they’re going to pay 20 bucks a month. You know, they, you know.

Christian Swain (31:48)

Well, there’s got to be money for them. Yeah.

Jay Nachlis (31:51)

Right, right. Well, the one fly in that ointment that I’m asking about though, because that makes total sense to me logistically, except for the fact that you’re not going to just use music and ideally a music podcast. You might have a sports podcast or a comedy podcast. Okay, right.

Peter Ferioli (32:05)

But has to start somewhere. Let’s start there. Okay, you are correct. But we have to build the use case and create some guardrails first for the rights holders to go, yes, these are people who are legitimate in the music industry to push music. They’re verified. We know they’re in that category. We can throw them out of that category. If they’re abusing our music, we can contact Apple or whatever it is. We can contact Libsyn and go, no, they’re not really in the, you know, they’re using this song for entertainment purpose, whatever it is. I was just starting at a beginning. Yes, you’re correct that scale.

Jay Nachlis (32:34)

Got it, got it.

Peter Ferioli (32:35)

Outside of the music category, but we need to start with something that is going to work.

Christian Swain (32:43)

All right, Jay. Thank you

Jay Nachlis (32:44)

All right, Thanks, guys.

What a difference a few weeks, days and hours makes.

What a difference a few weeks, days and hours makes.