When I programmed radio stations, I would occasionally run a “quarter-hour test” of my stations and the competition. This practice allowed me to step outside my usual listening patterns, which were highly unusual compared to that of a typical listener. The quarter-hour test was a way to force myself to create random snapshots of listening, in the same ways a listener may pop in and out. When I ran a quarter-hour test, I wasn’t thinking about the hourglass PPM stopset strategy, where contests were running, or where a commercial-free sweep took place. A quarter-hour test is outside-in listening…starting a quarter-hour when I thought about it, rather than scheduling when my listening would take place.

Several years ago, I ran quarter-hour airchecks for the streams of local radio stations, and it was hard to get past the clunkiness that existed, with spots, jocks, or music getting cut off. Now in 2023, as the industry watches the incremental growth of radio listening via streaming rather than with an AM/FM radio, I ran an updated quarter-hour test of four radio stations across the United States to get a glimpse of how local radio is adapting to the changing habits of its listeners.

The good news? Listening is far less clunky and more seamless than the last time I ran the test. The four stations I monitored, with only one exception, had high-quality streams with smooth transitions.

My listening experience, however, unearthed bigger obstacles for local radio. Some won’t necessarily surprise you, but I’ll challenge you to view them from a different lens and perspective.

My streaming quarter-hour test included four radio stations each in a different format and broadcasting from a different region of the country. One is a Country station in the Midwest; another is a Hip Hop station in the West; the third is a News Talk station in the Northeast; and the last one is a Classic Hits station in the South. I made sure to listen to stations on different streaming platforms. I picked random times to listen, spanning mornings, middays, and afternoons.

I started a timer for 15 minutes from the time I started the stream to the time I logged off, and then started taking notes.

MIDWEST COUNTRY TEST

At 10:07a local time, the stream went right into a song, just as if I were listening on a radio. This was followed by a live and recorded contest solicit into a second song. At 10:14a, the jock did a backsell and some content, and teased upcoming artists.

The stopset lasted seven minutes and featured 12 spots. With no imaging or station identification out of the commercial break, the stream went into a third song, during which the quarter hour of listening concluded.

Recap:

10:07-10:22 3 songs, 2 station mentions, 12 commercials.

WEST HIP HOP TEST

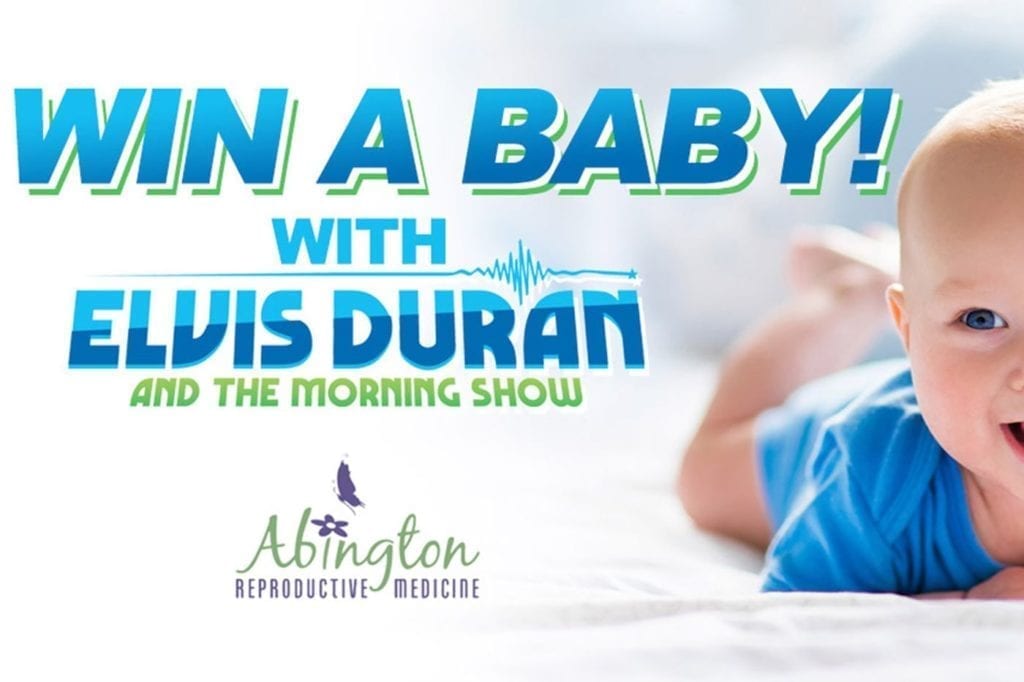

At 9:43a local time, my streaming experience again started with a song. This went right into a live jock bit with no station identifier. Another song played into a contest promo and station positioner at 9:52a. And then…18 commercials in a row. I listened past the 15-minute mark just to see when the stopset would end, which it finally did with yet another contest promo at 10:02a (at the 19-minute listening mark).

Recap:

9:43-10:02 2 songs, 1 station mention, 18 commercials

Teenage boy in disbelief that the 16th commercial isn’t the last one

NORTHEAST NEWS TALK TEST

This afternoon drive experience began at 3:05p and was the only one of the four tests to begin with a pre-roll video and two spots. One minute later, it rolled directly into the host in the middle of election talk. At 3:11p, the announcer threw it to a traffic report that ended with an awkward cutoff transition to spots, reminiscent of the clunky experiences from years ago. In this case, the station played two spots, a weather update with a station identifier, one more spot, a station identifier and positioner, and back to the talent with more election talk. I thought it was clever to break up the short commercial break with service elements, which kept my attention.

Recap:

3:05-3:20 11 minutes of content (including traffic/weather), 3 station mentions, 3 commercials

SOUTH CLASSIC HITS TEST

There was some friction at the beginning of this listening experience at 12:29p, as I clicked on a big “play” button that didn’t immediately play the station as I would have expected. It took me some time to find yet another play button on the screen to actually get the stream to trigger and start playing.

And in this instance, the station was in the middle of a spot break, with seven commercials in a row before playing a specialty programming sweeper and quick live break at 12:33p. The next 11 minutes were music intensive, with three songs boasting a quick sweeper or live break in front.

Recap:

12:29-12:44 3 songs, 3 station mentions, 7 commercials

As a listener, I was very pleased overall that each of the four listening experiences was generally seamless.

As a researcher, I’m going to bring up challenges that I perceive these listening experiences brought to light.

Here are three takeaways from this radio streaming quarter-hour test.

- Should every stream have “welcome branding”?

Sure, if I tune into a station on an AM/FM radio, I’ll get what I get at that time. But streaming enables the opportunity to make a brand statement immediately, which is particularly valuable as brand-building opportunities are at a premium.

- Should we ever run 18 spots in a row?

No, it wasn’t 18 minutes of commercials. Yes, I’m aware the station was likely playing the backloading game, throwing an absurd number of spots at the end of the 9am hour so the morning show could have less spots earlier in the show. But as I mentioned earlier, the quarter-hour test is designed to be outside-in listening. The listener doesn’t know or care about the backloading strategy, and as a listener 18 commercials in a row is awful. There is literally no way I would stay until the end if I was doing any sort of active listening.

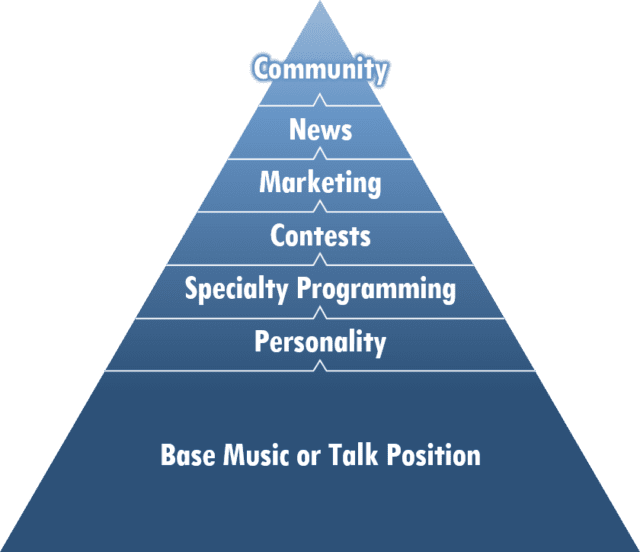

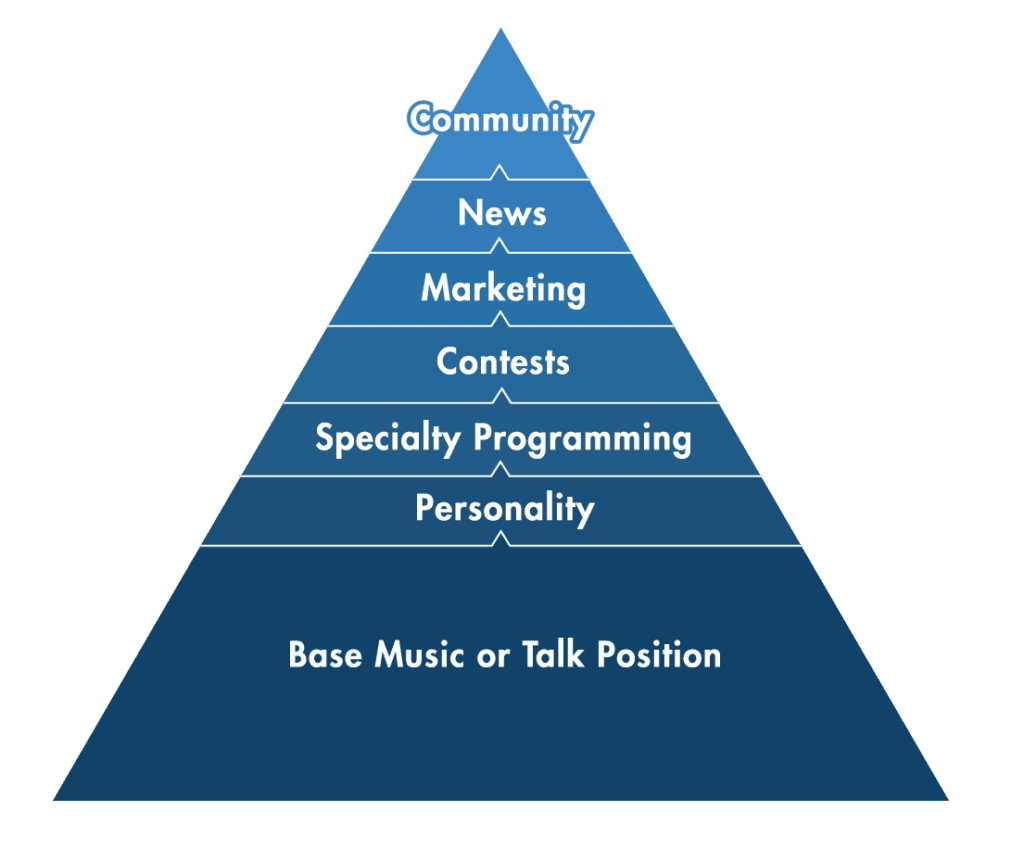

- Are we effectively building our brands in each quarter hour?

This is the most important question. If a local radio station is to compete in the streaming space, it must do three things well. First, it must offer a streaming experience that isn’t inferior to other DSP experiences. Second, it must accurately reflect the listening experience one would expect on an AM/FM radio. Third, it must effectively find ways to grow its brand without friction caused by the streaming experience.

This last point is especially important because radio’s challenges are too often framed in simplistic “too many commercials”-type arguments.

Rather, let’s change that perspective to consider how self-imposed obstacles can impede brand awareness, the building of strong images, and the creation of bonds with our talent.

Regularly monitor the over-the-air feed and stream, utilizing the quarter-hour test to answer those as questions:

- Did I build brand awareness (do listeners know who we are)?

- Did I build strong images (do listeners clearly know what we’re known for)?

- Did I build bonds with our talent (did they make an impression)?

Remember to focus on creating an outside-in listening experience and when possible, follow up with strategic research to track the effectiveness of your efforts.