Don’t get radio talent coach Steve Reynolds started on deep tracks. Wait, it’s too late. It all started June 2nd at 11:53am on his Facebook page, when he posted this:

“Dear Yacht Rock Radio on SiriusXM: welcome back, happy summer, missed you, but…you’re playing lots of unfamiliar music and songs that are stiffs. Please get back to the cheesy, known songs only.”

That initial post regarding the seasonal soft rock channel inspired 41 comments, including chime-ins from some pretty big name radio people.

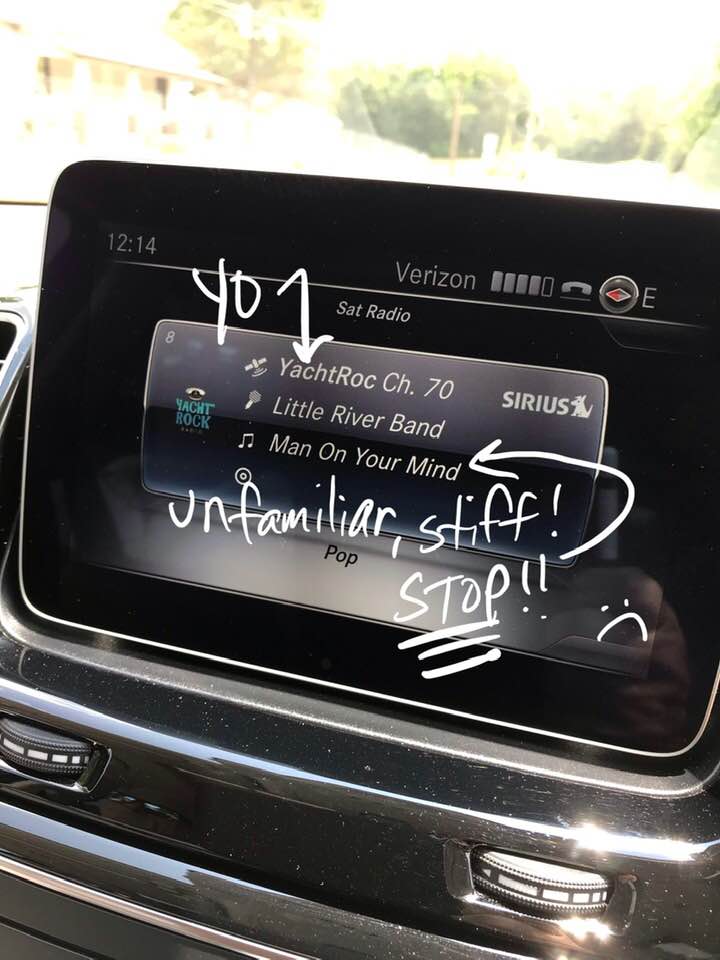

But Steve was just getting started. An hour later he posted this:

A few days later, he asked his followers to “report all non-yacht songs heard on Yacht Rock Radio,” a post that resulted in 80 comments.

To date, the topic has generated hundreds of comments. We were intrigued enough to cover the topic in this week’s blog.

Steve takes issue with two separate points in his posts. One is the playing of “stiffs”, or unfamiliar songs, and the other is songs that he feels don’t make sense on the station.

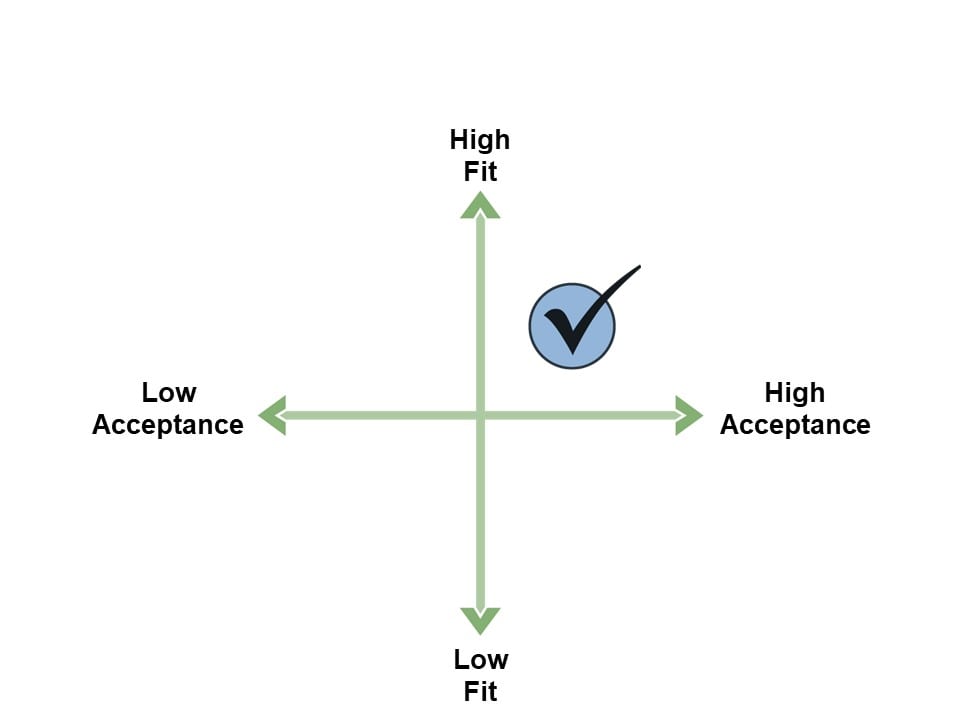

The Fit measurement we use in our FACT360 Strategic Music Tests can tell you when a song may not be in sync with your brand. I covered this topic in the blog, “Should I Play That Song On My Radio Station”.

When it comes to the former issue, whether or not to play deep tracks, here is an absolute truth—every radio program director or music director, at some point or another, has felt the allure of playing lesser-known songs or songs that weren’t hits on their station. It may be a caller on the request line, a salesperson or the programmer questioning himself. And when a PD has to make the decision on whether a deeper track makes sense, the first questions to ask are:

- Who is your audience?

- Why are they listening to you and what are their expectations?

SiriusXM, for example, has a deep tracks channel, where the perception Steve noted on the Yacht Rock channel would be reversed. If you hear a hit on the deep tracks channel, that would not be delivering to expectation.

This aligns with the very reason why Steve explains he was inspired to write the post in the first place.

“Yacht Rock brings me back to a happy, carefree time,” he says. “The role of the Yacht Rock channel for me is nostalgia. When a comfortable, familiar song like ‘Deacon Blues’ by Steely Dan comes on, for example, it makes me smile. I don’t want to have to use brainpower when I’m in this state. When a song comes on I’ve never heard of in this context, now I’m using parts of my brain to think about whether I know it and what I think of it. That’s not why I’m there.”

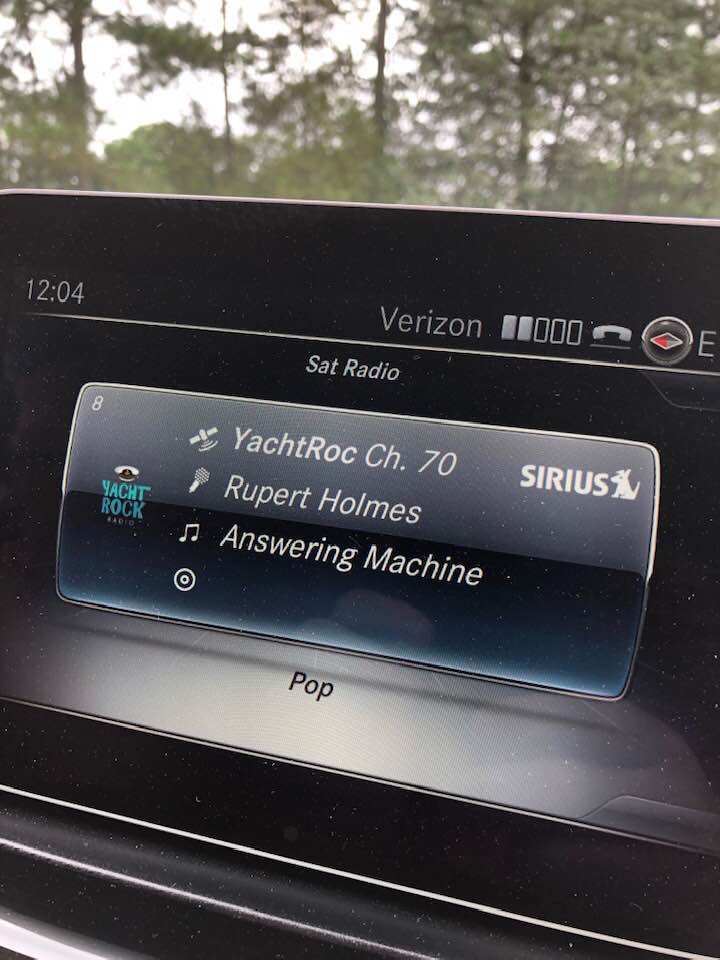

Rupert Holmes has one hit with staying power. This isn’t it.

Context plays a crucial role. AAA stations often have perception of more depth that may allow them to go deeper than a Hot AC station, for example.

If listeners expect their favorite songs on your radio station, the only way to satisfy them is by playing something familiar. But with deep tracks you can’t do that because the very premise of a “deep track” is that you can’t find one that appeals to everyone.

Here’s another example:

Years ago, I drove across the country listening to Creedence Clearwater Revival. I love CCR. My deep is CCR, so I can listen to songs that are unfamiliar to most. For a Classic Rock fan, someone else’s deep may be The Eagles and another’s may be Aerosmith. For a hit music station, the expectation, of course, is hit music.

We are in the business of satisfying customers (listeners) that come to our stores (stations).

We know through research that you can’t find any song—even the biggest, most popular hit song—that appeals to all your listeners.

And you certainly can’t find a deep track that appeals to all of them. Why would you minimize the percentage of customers that are likely to be satisfied?

Steve Reynolds makes a living coaching radio personalities, and he sees a parallel between program directors deciding which music to play and air talent deciding which content to feature.

“As you’ve said many times, Jon, every song is a marketing decision. Is that the song you want representing your radio station? Not just some songs. Every song. I tell air talent, every second of time you have on the station is like beachfront property. You’re the developer. What will you erect on the property? Is it the 4-story home with panoramic views of the ocean and a pool or is it an apartment with no views? Are we selecting our very best, most appealing content every time? It’s the same thing with songs. Are we playing our best, most appealing songs every time? If not, why?”

This doesn’t mean that you never take chances and color outside the lines. As referenced in “Should I Play That Song On My Radio Station,” you can be entrepreneurial in your own lane. You can’t be entrepreneurial in your fringe lanes.

As Don Benson, the former CEO of Lincoln Financial Media puts it, your format lane gives you license to introduce your audience to songs and even sounds they haven’t heard. When you play outside your lane, you risk losing listeners and may encourage brand erosion.

So when it comes to deep tracks, determine:

- Who is the audience?

- Why are they listening to you?

- What are their expectations?

If, in this framework, playing deep tracks makes sense, great.

If not (and it most cases it will be “not”), remember you’re in the customer service business. Providing the most appealing product is the key to success.